The Plague of Caste in Menstruation

“Pollution may be temporary or permanent, voluntary or involuntary and may fall on any member of the society. The first and the later menstruations as well as delivery are periods of specifically female pollution (even though women’s impurities may spread to others) of the involuntary type.”

This line of thought and belief, as noted by Gabriella Eichinger Ferro-Luzzi in her work ‘Anthropos’, was reflective of the menstrual scene in Tamil Nadu back in the 1970s. It has been noted that during the time of a woman’s “impurity”, she was reduced down to an untouchable. The menstruating woman was prohibited from coming in contact with other people as well as objects and this fear rose from the lack of knowledge surrounding the natural biological process. This gives us an idea of the fantastical apprehension that surrounded vaginal blood and how menstruating women were (and still are) considered to be the lowest of the untouchables, also known as ‘Candala’.

Assigning the menstruator a small corner in the house or, in most cases, an outhouse, was and still is a common practice. With no proper menstrual products at their disposal, women have little choice but to resort to unhealthy practices of using mud and sand as substitutes. Evidently, we see the need for temporary segregation of the menstruators taking a seat above the need for menstrual health and hygiene. However, more striking is the fact that it is only a certain section of women in the society who are subjected to such discriminatory extremes. That section constitutes women belonging to the lower castes.

Chauvinism, alienation due to menstruation, general subjugation, and the 12% GST on sanitary napkins are some of the common problems faced by most Indian women yet, the average upper-caste women in urban and semi-urban areas are still more fortunate than the vast majority that includes both lower caste men and women.

While it is important to speechify menstruation and fight taboos that restrict the mobility of women during periods, it is equally important to understand that women’s experiences of menstruation cannot be homogenised.

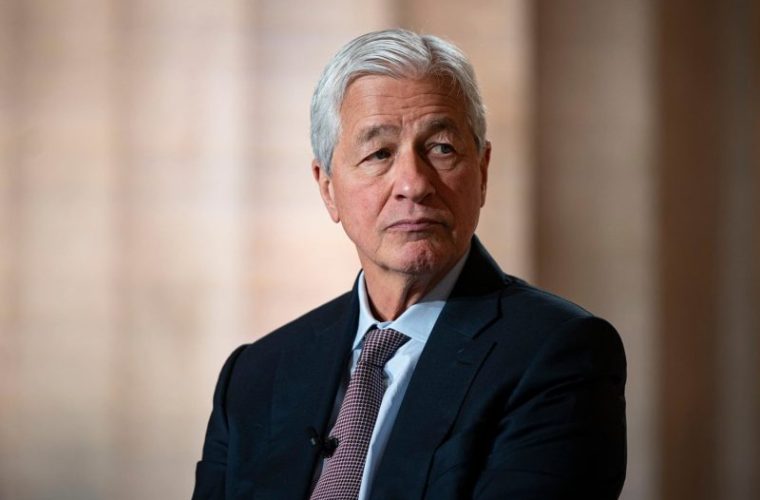

A notice board outside a Jain Temple. Source: Getty Images

Upper caste women are not allowed to enter temples during menstruation, as it is believed to affect caste purity and purity of the household. This is in sharp contrast to the eternal untouchable condition of Dalit women who are not allowed in temples throughout their lives. It is as though they are not entitled to ritual purity or self-respect. A major chunk of lower-class women cannot even afford the luxury of cloth or underwear to soak their blood, and often end up using and reusing their ‘cholies’ till the very end. A survey conducted by the National Family Health Survey-4, released in 2015-16, revealed that while in urban India, 77.5% women observe safe menstrual practices, the numbers stand at an average of only 48.2% for women in rural areas. Inaccessibility of proper sanitary products leads to menstrual infection in 14% women. Owing to India’s inefficient waste management methods, these used sanitary products always end up in the common dumping grounds or ‘dhapas’ where unequipped sanitary workers (mostly men) are required to scavenge and segregate menstrual wastes as much as possible. Similarly, in most cases, the women who are employed as cleaners in the public and the corporate sectors, by and large, belong to the lower castes. In 2014, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 100 people currently or formerly working as manual scavengers, in the Indian states of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. The survey revealed that women involved in cleaning dry toilets in rural areas often weren’t paid cash wages, but instead, as a customary practice, received leftover food, grain during harvest, old clothes during festival times, and so forth – only at the discretion of the households they served. The facade of class distinction comes into play as well when clothes used during menstruation are deliberately given to the ‘dhobis’, belonging to lower caste and class, to wash. This is more like an act of directing the ‘evil’ and the ‘impurities’ towards those who do not belong to the class of the ‘privileged’. As stated by Gopal Guru in his work “Archaeology of Untouchability” (2009),

“Just imagine what would happen to the touchable, if the untouchable were to refuse to become the dumping ground for somebody’s moral dirt or refuse to illuminate the touchable. It perhaps would lead to the moral decomposition or atrophy of the touchables’ body or they would get crushed under the accumulated weight of these impurities. (Thank god, there has been an untouchable around to carry this burden!)”

Such an insolent statement was made in reference to a tradition which is still followed in Andhra Pradesh; the stained clothes worn by an upper-caste girl at the onset of her active menstrual cycle is usually given to the Chakali (lower caste) women. This serves as a primary example of how the upper-caste wanted to keep themselves ‘pure’ by directing the ‘impure’ towards the lower-castes.

Debates about period leaves have occupied a major space in social media and elite circles today, but the lowest strata of the society is never brought to the forefront of these discussions. Have we ever talked about availing period leaves to our very own domestic help – maids, cleaners, sweepers?

These women have to not only suffer through the ordeal of menstruating in the absence of proper sanitary options but also be subjected to unimaginable social discrimination fueled by illiteracy, lack of awareness, stigma, and deeply etched patriarchy.

“If the market can solve the issues of menstrual taboo in India by producing sanitary napkins, it could have solved the question of untouchability by producing soaps, detergents, and sanitisers.

By Sukanya Chaudhury and Sejal Nathany