Lockdowns Are More Economically Devastating Than Voluntary Social Distancing

Once again, several European countries have extended and tightened lockdowns, despite the continent having been under recurrent strict confinement measures since the beginning of the pandemic. The population watched in disbelief how new restrictions were added to the already heavily curtailed access to restaurants, bars, cultural gatherings, sport events and international travel. The authorities are repeating the same narrative to justify the new measures—a spike in covid-19 cases threatens to overcrowd hospitals, while the media blames the fiasco on the spread of new virus strains or slow vaccination campaigns. In reality, this is yet more proof that lockdowns are not the solution to the covid-19 crisis. Ryan McMaken makes a strong case that restrictive lockdown measures further reduced economic activity beyond the effect of normal voluntary social distancing without producing any additional health benefits during the pandemic. This invites the obvious question why, after more than one year of pandemic, mandatory lockdowns are still perceived as a “silver bullet” when voluntary self-protection against the virus would work better. In principle, individuals using their own judgment are likely to adjust more efficiently their business and social behavior to the perceived health risk, thus reducing the burden of social distancing.

This question becomes almost rhetorical if we think about the inherent drive of governments and politicians to control the conduct of businesses and citizens. They could not miss the opportunity of the covid-19 crisis. And in order to support them, mainstream analysts spare no efforts to come up with unexpected theories and arguments. In chapter 2 of its latest World Economic Outlook the International Monetary Fund argues that “lockdowns and voluntary social distancing played a near comparable role in driving the economic recession” and warns “against lifting lockdowns prematurely in hope of jump-starting economic activity.” In other words, it was not mandatory lockdowns that drove many economies to the ground during the pandemic, but the fear of contracting the virus, which led many people to reduce social contact. Moreover, the IMF concludes that “lifting lockdowns is unlikely to rapidly bring economic activity back to potential if health risks remain” and “medium-term gains may offset the short-term costs of lockdowns, possibly even leading to positive overall effects on the economy.” So, what the IMF claims is that lockdowns bear little or no economic cost because in their absence the epidemic would have wreaked havoc through the economy anyway.

Before showing that the IMF’s analysis flies in the face of reality, one cannot help noting that their overall claim is counterintuitive. If the IMF’s models are correct and lockdowns and voluntary social distancing have played a similar role in reducing mobility and economic activity during the pandemic, why would the former be necessary at all? Even if lockdowns are allegedly not causing additional economic pain, they certainly have a psychological cost, which reduces people’s welfare. Moreover, there is a nonnegligible legal compliance cost both for the police and the taxpayer.

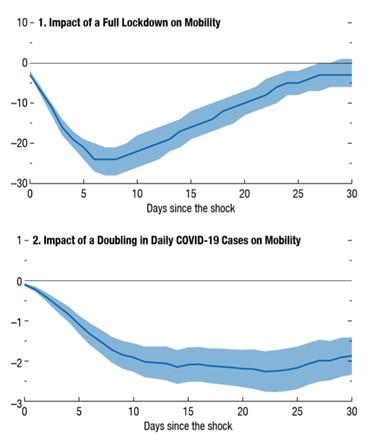

The IMF’s claim is based on a quantitative analysis of the impact of lockdowns and voluntary social distancing on mobility. According to it, applying a full lockdown that includes stay-at-home requirements, business and school closures, and travel restrictions reduces mobility significantly, by about 25 percent within a week. Afterwards, mobility would resume gradually as the “lockdown tightening shock dissipates.” But people are also likely to reduce exposure to one another on a voluntary basis when the number of cases increases. In this case, the IMF estimates that a doubling of daily cases reduces mobility by about 2 percent within two to three weeks, after which the effect starts to dissipate (graphs 1 and 2). The IMF further concludes that during the first three months of the pandemic, both lockdowns and voluntary social distancing had a large and roughly similar impact on mobility, with a smaller contribution from voluntary social distancing in low-income countries and a larger one in advanced economies.

Graphs 1 and 2

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook: A Long and Difficult Ascent (Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, October 2020).

One should always take modelling results with a grain of salt, but in this case it is difficult to see how a drop in mobility of about 25 percent within a week could be roughly equal to a decline of about 2 percent within two to three weeks, given historic trends in the number of daily cases. For example, US statistics show that, between April and October 2020, the number of daily new covid-19 cases doubled only once at the beginning of the summer (graph 3). Subsequently, the number of cases increased about five times from November 2020 to January 2021, which is clearly not enough to put lockdowns and voluntary social distancing on the same footing in terms of impact on mobility. In particular because the increase in the number of daily cases went almost hand in hand with the rise in the number of daily tests from April 2020 until January 2021. More testing automatically yields a higher number of cases but not necessarily a larger spread of the disease if diagnosing a case does not require clinical symptoms. In addition, false positive tests are also commonplace, which makes us wonder how this kind of increase in “cases” would change the social distancing behavior of people. Finally, the IMF analysis shows that the lockdowns’ negative impact on mobility dissipates much faster than that of voluntary social distancing. It means that over time people will do their best to get around rules they don’t believe in, further weakening the case for mandatory lockdowns.

Graph 3

Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

A cursory look at developments in several major economies shows that government lockdowns are the main driver of the fall in mobility and economic growth during the pandemic. According to the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT), France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the US suffered from stricter lockdowns than Japan, Switzerland, Korea and Sweden. This seems consistent with anecdotal evidence and independent reports. At the same time, according to the population mobility trends provided by Apple the same group of economies with more severe lockdowns recorded lower population mobility, on average, both in terms of walking and driving (graphs 4 and 5).

Graph 4

Source: OXFORD COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) and Apple Mobility Trends (Average, January 2020–February 2021, own calculations).

Graph 5

Source: OXFORD COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) and Apple Mobility Trends (Average, January 2020–February 2021, own calculations).

As these indicators are just aggregate proxies which cannot capture reality in full, there are also less clear-cut cases requiring further clarifications. Korea appears to display low population mobility despite fairly light lockdown measures, which seems puzzling. A second mobility indicator provided by Google shows that in reality Koreans managed to carry on their usual activities with least disturbances compared to the prepandemic situation. Korea performed much better than its peers by almost all mobility metrics, including visiting workplaces, time spent at home, use of public transport, shopping and visiting places of recreation (graphs 6–11). It only trailed the peer group in terms of visits to parks and outdoor spaces, which may indicate that by preserving almost normal movement patterns, trips to local parks and gardens were less needed. Korea has benefitted from extensive early testing to detect and isolate potential cases and a well-prepared health sector. The US and Germany also exhibited relatively high mobility according to the Apple index, but unlike Korea, they appear as having had strict lockdowns. In the case of the US, the lockdown stringency seems to have affected working arrangements and time spent at home, rather than travel for shopping and recreation. Together with a lower volatility of mobility and lockdown strictness than in Europe, the US’s data points to a better continuity of business and social life. On the other hand, Germany enjoyed higher mobility at the beginning of the pandemic, which worsened considerably once it entered a strict and lengthy lockdown in November 2020. Overall, despite intrinsic limitations, these indicators clearly show that lockdown stringency correlates well with population mobility, either when comparing different countries or different points in time within the same country.

Graphs 6–11

Source: Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Trends. Our World in Data.

As strict lockdowns tend to reduce population mobility and business activity more, they also have a more negative impact on economic growth. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development data shows that real GDP fell dramatically, by close to 10 percent or above, in France, Italy, Spain, and the UK in 2020. The output growth differential between 2019 and 2020 has been more than double in these countries compared with peers that had higher population mobility (graph 12). At the same time, Korea, Sweden, and Switzerland were the best economic performers during the pandemic while having some of the lightest lockdowns.

Graph 12

Source: OECD.Stat.

Conclusion

The IMF’s claim that mandatory lockdowns and voluntary social distancing played a similar role in driving the economic recession during the pandemic seems mostly unfounded. Available data shows that severe lockdowns reduced population mobility and hampered economic growth more than milder ones. As several studies question also the alleged benefits of lockdowns in suppressing the pandemic, they should be lifted instead of extended or tightened. The main reason to maintain them seems to be the failure of socialized medicine to deal with peaks in the number of covid-19 cases. Yet, it is almost inconceivable that after more than one year since the start of the epidemic some of the world’s richest countries cannot ensure sufficient hospital ICU beds and are lagging far behind in terms of vaccinations. In that case, the logical response would be not to expand government intervention further, but to unwind the initial one, i.e., deregulate and privatize healthcare.