Printing Money Can’t Replace Real Savings

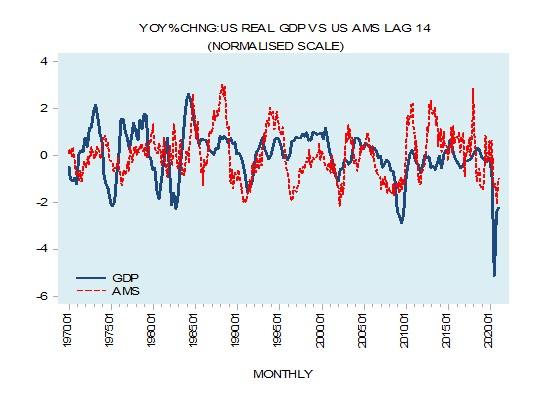

Between January 1970 and December 2020 on average changes in money supply preceded changes in real economic activity by fourteen months, as depicted by real gross domestic product (GDP). Based on this it is tempting to suggest that a strengthening in the growth rate of money supply will result in the strengthening of real economic growth. Conversely, a weakening in the growth rate of money supply will set in motion a decline in real economic activity.

The relationship between the growth rate of money supply and the growth rate of real GDP presented in the graph above is a display of historical information. But history as such cannot confirm that increases in the money supply growth rate can set in motion real economic growth. According to Ludwig von Mises, in Human Action,

History cannot teach us any general rule, principle, or law. There is no means to abstract from a historical experience a posteriori any theories or theorems concerning human conduct and policies.

Also, in the The Ultimate Foundation of Economic Science, Mises argued,

What we can “observe” is always only complex phenomena. What economic history, observation, or experience can tell us is facts like these: Over a definite period of the past the miner John in the coal mines of the X company in the village of Y earned p dollars for a working day of n hours. There is no way that would lead from the assemblage of such and similar data to any theory concerning the factors determining the height of wage rates.

In order to maintain their lives and well-being people require final goods and services and not money as such, which is just the medium of exchange. Money only helps to facilitate trade among individuals— it does not generate any real stuff. According to Rothbard in Man, Economy, and State,

Money, per se, cannot be consumed and cannot be used directly as a producers’ good in the productive process. Money per se is therefore unproductive; it is dead stock and produces nothing.

Paraphrasing Jean-Baptiste Say, Mises wrote,

Commodities, says Say, are ultimately paid for not by money, but by other commodities. Money is merely the commonly used medium of exchange; it plays only an intermediary role. What the seller wants ultimately to receive in exchange for the commodities sold is other commodities.1

Again, being the medium of exchange, money enables the goods and services of one individual to be exchanged for the goods and services of another individual. This means that with the help of money we can exchange something for something else.

When money is generated out of “thin air,” it means that nothing was produced to secure the newly generated money. This means that nothing was exchanged for the newly generated money. Once this money is employed in exchange for goods and services, it sets in motion an exchange of nothing for something. Individuals who are in the possession of the newly generated money can now divert to themselves goods and services without any contribution to the production of these goods and services. What we have here is the so-called money counterfeit effect. A counterfeiter by generating bogus money, which masquerades as money proper, can divert real wealth to himself without any contribution to the pool of real wealth.

The increase in money out of “thin air” sets in motion a process of impoverishment of wealth generators, i.e., those individuals who have contributed to the pool of goods and services. Hence, rather than causing economic growth, the money out of “thin air” is setting in motion the process of economic impoverishment and a weakening in real economic growth.

Money Supply Growth and Economic Busts

For most commentators the arrival of a recession is due to unexpected events, such as the coronavirus pandemic, that push the economy away from a trajectory of stable economic growth. Unexpected events or shocks weaken the economy, so it is held. But a recession is not about the strength of an economy as such but about the liquidation of various nonproductive activities. Here is why.

As a rule, a recession or an economic bust emerges in response to a decline in the growth rate of money supply. Usually this takes place in response to a tighter monetary stance of the central bank. As a result, various activities that sprang up on the back of the previous strong money growth rate come under pressure. These activities cannot support themselves—they have emerged because of the support that the increase in money supply provided by diverting real wealth to them from wealth generators. Consequently, this weakens wealth generators.

A tighter monetary stance by the central bank, and the consequent decline in the growth rate of money supply, slows down the diversion of real wealth. This in turn undermines various nonproductive undertakings.

A recession, then, is about the liquidation of various nonproductive, i.e., bubble activities, because of the decline in the diversion of real wealth from wealth generators to them. Again, this decline in the diversion emerges once the money supply growth rate slows down or declines.

GDP Paints a Misleading Picture

Economic growth presented by government statisticians is in terms of data such as gross domestic product (GDP). The latter indicator is designed along the lines of the Keynesian framework, which equates monetary spending with income. In this thinking, more spending leads to a higher national income and in turn to a higher economic growth.

Following this logic, a tighter monetary stance by the Fed leads to a slower economic growth, while increases in money pumping produce higher economic growth. A stronger growth rate of money supply leads to a stronger pace of expenditure. (In the GDP framework, this results in an increase in overall income in the economy and hence in a higher GDP growth rate.)

In reality, the exact opposite actually takes place—printing more money weakens wealth generators’ ability to grow the economy, while a decline in the money supply growth rate strengthens their ability to grow it. Once the central bank raises the pace of monetary pumping in order to lift the economy from a recession, this arrests the demise of various bubble activities. It also gives rise to new ones.

An outcome of the so-called economic growth in terms of GDP is nothing more than the strengthening of the consumption of wealth and the impoverishment of wealth generators. All this undermines the process of wealth generation and weakens real economic growth. Because of the increase in the money supply growth rate, the erosion in the real wealth formation process is not always portrayed by the GDP data. Once however, the pool of real savings—the heart of economic growth—starts to decline, the real GDP growth rate is likely to follow suit (see discussion on this below).

Real Saving and Economic Growth

At any point in time the number and the size of activities that can be undertaken is determined by the pool of real savings. This pool comprises final consumer goods.2 Note that this pool sustains individuals who are engaged in the enhancement and the increase of the infrastructure. This pool also sustains individuals who are engaged in the production of final consumer goods.

The improved infrastructure permits the increase in the production of intermediate goods, the increase in the production of services, and the increase in final consumer goods. Once an increase in the production of final goods and services happens, this increase can then support a corresponding increase in the demand for final goods and services. Note that one must produce something useful before demanding things.

Observe that this runs contrary to the GDP framework, where the increase in monetary expenditure strengthens the demand for final consumer goods and services, in turn triggering an increase in the supply of these goods and services (i.e., demand creates supply). If, however, the infrastructure is not enhanced and expanded, it will not be possible, all other things being equal, to increase the production of final consumer goods and services and therefore to accommodate the increase in the demand. Hence, an increase in demand will not automatically result in an increase in supply. Because the supply of goods is taken for granted, the GDP framework completely ignores the importance of the various stages of production that precede the emergence of the final consumer goods.

In the real world, it is not enough to have demand for final consumer goods—one must have various intermediate goods that are required in the production of final consumer goods. The intermediate goods are not readily available; they have to be produced.

Observe that individuals, whether in productive or nonproductive activities must have access to real savings in order to sustain their lives and well-being. As long as wealth producers can generate enough real savings to support productive and nonproductive activities, loose monetary policies will appear to be successful.

Over time, however, a situation can emerge as a result of the persistent loose monetary policies where there are not enough wealth generators left and generated real savings are consequently not large enough to support an increase in real economic activity.

Once this happens, the illusion that easy monetary policy can grow an economy is shattered—real economic growth must come under pressure. Even in terms of real GDP, which mirrors monetary changes, it will be difficult to show economic growth. The only reason why real GDP could display a rising growth rate during such an event is that misleading price deflators are employed that understate the true rate of price increases. If the Fed were to accelerate its monetary pumping while the pool of real savings is declining, it runs the risk of further depleting the savings pool.

Those commentators who subscribe to the view that the acceleration in money pumping could revive real economic growth imply that something can be generated from nothing. Printing more money, however, cannot replace real savings. If stimulatory monetary policies could strengthen real economic growth, then world poverty should have been eliminated a long time ago.

- 1. Ludwig von Mises, Lord Keynes and Say’s Law: The Critics of Keynesian Economics, ed. Henry Hazlitt, (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1983), p. 316.

- 2. Real savings is the amount of final consumer goods produced minus the consumption of these goods by those who produce them. Thus, if a baker produces ten loaves of bread and consumes two loaves, his real savings are eight loaves of bread.