The Biggest Threat to US Hegemony: China, Russia, or Debt?

Now that the Biden administration has settled in, it is time to reassess American policy towards Russia, China and the wider Asian scene. Is it going to be a continuation of the Trump administration’s policies, or is there something new going on? Given the continued tenure of staffers at the Pentagon from before the Trump presidency, it seems unlikely there will be much in the way of détente: it is game-on for the cold war to continue.

Before delving into geopolitics, we must be careful to define a neutral position from which to observe developments. You cannot be objective in these matters if you justify an uninvited invasion of a foreign territory to take out a proclaimed public enemy, as America did with Osama Bin Laden and then condemn Russia for attempting to murder an ex-KGB officer living in Salisbury, or for that matter the dismembering of a journalist in the Saudi Embassy in Turkey. You must be aware that it is an established part of what Kipling called The Great Game, and always has been.

Acts of this type are the product of states and their agents acting above any laws and are therefore permitted to ignore them. We must dismiss from our minds the concept that there are good and bad guys—when it comes to foreign operations, they all behave the same way. We must dismiss nationalistic justifications. Nor can we believe propaganda from any state when it comes to geopolitics, and particularly in a cold war. Know that our news is carefully managed for us. As far as possible we must work from facts and use reasoned deduction.

We are now equipped to ask an important question: the US status quo, with its dollar hegemony is seen by the new Biden administration as an unchallengeable right, and its position as the world’s hegemon is vital for … what? The benefit of the world, or the benefit of the US at the world’s expense? To answer this, we must consider it from the point of view of the US military and intelligence complex.

The problem facing us is that the Pentagon became fully institutionalized in managing America’s external security following the second world war. When the Soviets extended their sphere of influence into the three great undeveloped continents, Asia, Africa and South America, there was a case for defending capitalism and freedom—or at least freedom in an American sense by keeping minor nations on side. This was done by fair means and often foul for expediency’s sake.

But the fall of the Berlin Wall and the death of Mao Zedong made the American military and intelligence functions largely superfluous, other than matters more directly related to national defense. But it is in the nature of government departments and their private sector contractors to do everything in their power to retain both influence and budgets, and the argument that new threats will arise is always hard for politicians to resist. And what do the statists in a government department do when they have secured their survival? Their retention of power without real purpose descends into alternative military objectives. And from the first Bush president, they were all firmly on-message.

President Trump was the first president for some time not to start military engagements abroad. His attempts to wind down foreign operations were strongly resisted by defence and intelligence services. And his efforts to obtain a détente with North Korea were met with disdain—even horror at Langley.

Whatever the truth in these matters, it is highly unlikely that the power conferred by the ability to initiate unchallengeable cover-ups, information management, subversion of foreign states and secret intelligence operations is not abused. The proliferation and traction of conspiracy theories, attributed in their origin to Russian cyber-attacks and disinformation, is a consequence of one’s own government continually bending the truth to the point where large sections of the population begin to believe it is its own government’s propaganda.

This brings us to the change in administration. As a senator, Biden had interests in foreign affairs dating back to the late 1970s and was on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee from 1997 and subsequently became its chairman. As such a long-standing politician in this field it is almost certain that the Pentagon establishment regards Biden as a safe pair of hands; in other words, a president who is likely to support Langley’s role in setting geopolitical and defence priorities. Surely, for them this is a welcome change from the off-message President Trump.

Policies to Contain the Russian Threat

Despite the Navalny affair, Putin is still unchallengeable as Russian leader, having emerged from the post-Soviet turmoil where chaos and organised crime were the order of the day. No western leader has had such a tough political background and Putin is a survivor, a strongman firmly in control. This matters for America and NATO with respect to policies in Ukraine, the Caucasus, Syria, Iran and Turkey. Any attempt by America to complete unfinished business in Ukraine (a triparty scrap involving Russia, Germany/EU and the US over the Nord Stream pipelines depriving Ukraine of transition revenues is already brewing) is likely to lead to confrontations with Russia on the ground. And Russia signed a military cooperation pact with Iran in 2015. Like a cat with a mouse, Putin is playing with Turkey, interested in laying pipelines to southern Europe, and getting it to drift out of NATO. Russia’s interest in Syria is to keep it out of America’s sphere of influence, which with Turkey’s help it has managed to do.

For some time, military analysts have been telling us that we are now in a cyber war with Russia, accusing it of interfering in elections and promoting conspiracy theories—the US presidential election last November being the most recent assertion. As with all these allegations there is no proof offered, just statements from government sources which have a track record of being economical with the truth. Whatever the truth may be, cyber wars are closely intertwined with propaganda.

Attacks on Russia since the millennium have been by disrupting dollar payments, and less importantly, by sanctioning individuals close to Putin. The monetary threat was originally justified by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014, leading to the collapse of the rouble and a hike in interest rates. The new cold war had taken a financial turn. Russia’s response was to reduce the economy’s dependence on dollars as much as possible, with the central bank selling dollar reserves and adding gold in their place. It also set up a new payments system to reduce its dependence on the SWIFT interbank payments system.

Russia has survived all financial attacks and is now better insulated against them for the future. One-nil to the Russians. But the cost has been hidden, with western investment restricted to being mainly from the EU (particularly directed at the oil and gas industries). With the nation being fundamentally a kleptocracy, economic progress is severely constrained. Furthermore, with Russia being the world’s largest energy exporter, the west’s policy of decarbonisation is a medium to long term threat, leading to the demise of Russia’s USP. For these and other reasons Russia has turned to China as both a partner and an economic protector. In return, Russia is resource-rich, an energy provider, and therefore of great value to China.

Russia’s history of assassinating leading dissidents on foreign soil has been its greatest mistake. It took years after the Litvinenko assassination for diplomatic relations with the UK to be fully restored. The deaths of several Russian oligarchs in recent years on British soil were thought to be the actions of organised crime and not attributed to the Russian state. But the clumsy assassination attempt on Sergei Skripal in Salisbury by GRU officers three years ago is unlikely to lead to a rapprochement anytime soon.

The Russian and Chinese Geopolitical Partnership

One of the first persons to identify the geopolitical importance of Russia’s resources was Halford Mackinder in a paper for the Royal Geographical Society in 1904. He later developed it into his Heartland theory. Mackinder argued that control of the Heartland, which stretched from the Volga to the Yangtze, would control the “World-Island”, which was his term for all Europe, Asia and Africa. Over a century later, Mackinder’s theory resonates with the two leading nations behind the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

The underlying point is that North and South America, Britain, Japan and Australasia in the final analysis are peripheral and less important than Mackinder’s World-Island. There was a time when British and then American primacy outweighed its importance, but this may no longer be true. If Mackinder’s vision is valid about the overriding importance of undeveloped resources, Russia is positioned to become with China the most powerful national partnership on earth.

The SCO is the greatest challenge yet mounted to American economic power and technological supremacy. And Russia and China are clearly determined to ditch the dollar. We don’t yet know what will replace it. However, the fact that the Russian central bank and nearly all the other central banks and governments in the SCO have been increasing their gold reserves for some time could be an important clue as to how the representatives of three billion Euro-Asians—almost half the world’s population—see the future of trans-Asian money.

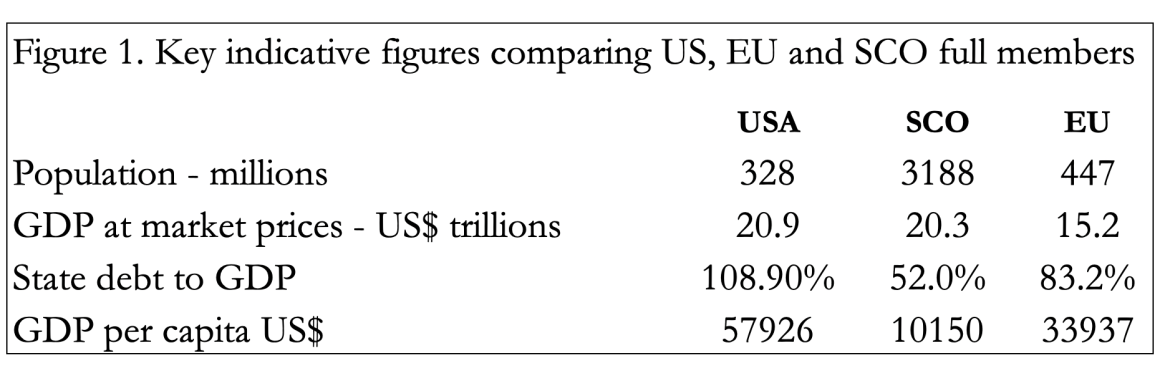

In terms of GDP per capita the United States is a long way ahead of the field. But it is also the most indebted at the national level. The difference with the SCO is at the purchasing power parity level, making market prices of secondary importance. While prices regionally vary considerably the costs of goods in the SCO are as an average considerably less than in the US and EU, so that on a PPP basis the SCO’s GDP is significantly greater than that of the US or the EU.

The inclusion of the EU in Figure 1 is a post-Brexit nod to the fact that the EU can no longer be automatically regarded as being in the US sphere of influence. The commercial ties to the SCO, with both energy reliance from Russia and silk road rail terminals in various EU states are clearly the trade future for the EU. The EU is advanced in its plans to bring national forces under its combined flag, which by giving them an EU identity can only loosen NATO ties with America. While not an active threat to America’s power, one can envisage the EU sitting on the fence in an intensifying cold war.

The SCO started life in 2001 as a security partnership between Russia and China, incorporating the ‘stans to the east of the Caspian Sea. Born out an earlier organisation, the Shanghai Five Group, it was set up to combat terrorism, separatism and extremism. It is still a platform for joint military exercises, but none have taken place since 2007 and it has morphed into a loose economic partnership instead.

Since the founding Shanghai Five, the SCO now includes India and Pakistan. Observer status includes Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran and Mongolia. These nations can attend SCO conferences, but their participation is very limited. Dialogue partners include Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Turkey. These nations can participate actively in SCO conferences, and this status is seen as a preliminary to full membership. Egypt and Syria have applied for observer status and Israel, Iraq and Saudi Arabia have applied to be dialog partners. Apart from South East Asian nations, which are dominated by a Chinese diaspora anyway, SCO members and their influence covers almost all of Halford Mackinder’s World Island, with the exception of the European Union.

This is the reality that faces American hegemony; there are twenty-one nations across Asia in a non-American alliance, or on the cusp of joining it. All the other European and Asian nations are within the SCO’s sphere of influence through trade, even if not politically affiliated. It is getting more difficult to define the nations definitely in the US pocket, other than its five-eyes partners (Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand). This simple fact places severe limitations on US action against China, and to a lesser extent Russia.

It is an exaggeration to suggest that an attack on one member state is an attack on them all. Their cooperation is fundamentally economic rather than military; except, as stated above, the SCO’s original function remains to eliminate terrorism, separatism and extremism. Indeed, India and Pakistan are at loggerheads over Kashmir, and China and India have border disputes in the Himalayas. But attempts, by, say, the US to prize India away from the SCO is bound to generate wider issues, and perhaps a response, from the other members.

The Biden presidency faces significant challenges in the ongoing cold war and America is unlikely to retain its hegemonic status. During Trump’s presidency, attempts to curtail China’s trade and technological development did not succeed, and has only emboldened both China and Russia to stand firm and as much as possible to do without America and its dollar.

Their senior advisors are, or should be, acutely aware of the debt and inflation traps facing the US and also the EU. Following the Fed’s policies of accelerated monetary expansion announced last March, China increased her purchases of commodities and raw materials, in effect signalling she prefers them to dollar liquidity. As a policy, it is likely to be extended further, given China’s existing stockpile of dollars and dollar-denominated debt. Her dilemma is not just the fragile state of the US economy, but that of the EU which on any dispassionate analysis is a state failing economically and politically as well. China will not want to be blamed for triggering a series of events which will get everyone reaching out for their forgotten copy of Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom.

As events take their course, the risk of a dollar collapse and a matching crisis in the euro, though for different reasons, increases. For Mackinder’s heartland theory to be proved and for the Russian and Chinese partnership to be in control of it, a mega-crisis facing the profligate money-printers must happen. All history and a priori economic theory confirm it will happen. The SCO’s Plan B will be a continuance of Plan A, hatched out of the Shanghai Five Group, making the World Island a self-contained unit not dependent on the peripherals—principally, the five eyes. For money, they must give up western ways with unbacked state currencies. Between them they have enough state-owned declared and undeclared gold to back the yuan, and the rouble. Give these two currencies free convertibility into gold, and they will be accepted everywhere, so their old cold war enemies can trade their way back to prosperity. The US has, or says it has, enough gold to put a failing dollar back on a gold standard, but for it to be credible it must radically cut spending, its geopolitical ambitions, and return its budget into balance. With luck, that is how the new cold war ends.