Biden Is Trying to Seize Control of Local Land-Use Regulations

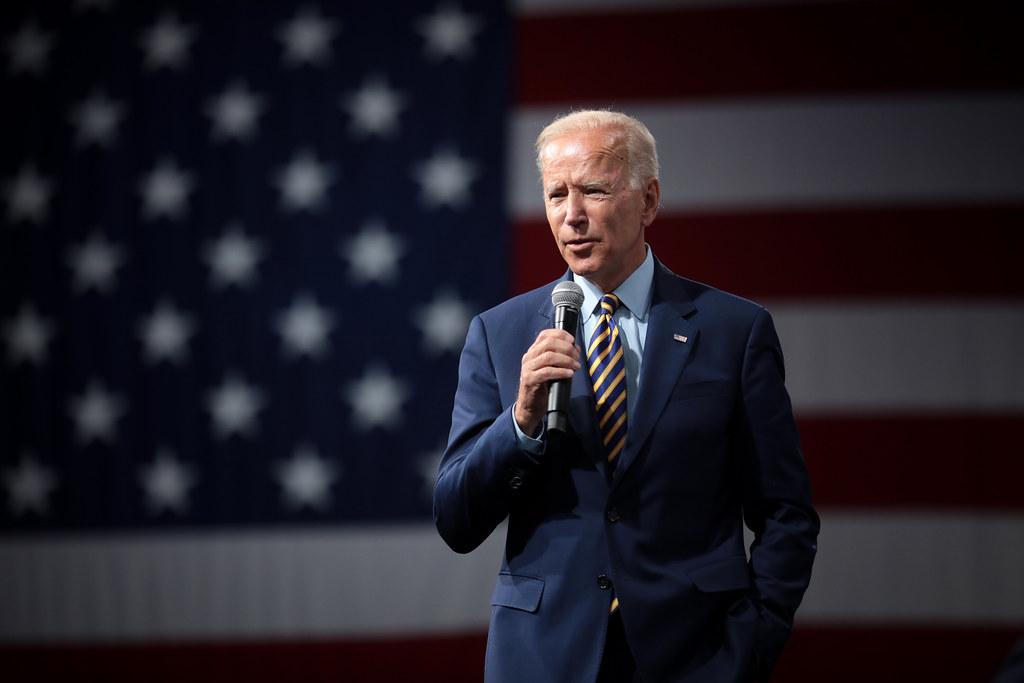

In recent years, there’s been a push to move zoning decisions further from the local level. In 2019, Oregon passed House Bill 2001, making it the first statewide law to abolish single-family zoning in many areas. By expanding the state government’s jurisdiction to include zoning decisions previously handled by local agencies, the law entails an alarming centralization of state power. This was quickly followed by the introduction of similar bills in Virginia, Washington, Minnesota, and North Carolina. Now President Biden is attempting to increase federal influence over local zoning.

Included in Biden’s American Jobs Plan is a proposal that would award grants to jurisdictions that move to eliminate single-family zoning and other land-use policies the administration deems harmful. Biden’s plan has been widely opposed by conservatives and libertarians alike, but some libertarians view this zoning proposal as the plan’s silver lining. These libertarians hope federal incentives will remove government obstacles to affordable housing. To be sure, government regulations at every level increase costs and violate property rights. However, political centralization will not reduce government. To the contrary, centralization must be understood as an expansion and concentration of state power. Instead of furthering property rights, centralization will promote a one-size-fits-all approach regardless of homeowner preferences.

At this point, some may object that unlike the laws introduced at the state level, Biden’s proposal could be resisted by simply refusing the grants. Indeed, a White House Official describes Biden’s approach to zoning as “purely carrot, no stick.” However, this offers little reassurance. Experience has shown that governments cannot be relied upon to refuse funding, and as Murray Rothbard points out, “[G]overnment subsidy inevitably brings government control.” Once the public becomes accustomed to the federal standards and local governments become dependent on the federal money, there’s little to stop them from accepting those same standards as laws. We need only look at education to see where federal subsidies can lead.

The zoning issue is instructive, because it demonstrates both how the federal government can seize control of local functions through the back door, and how a move from the local to state level can lead to further centralization. Given that centralization moves decisions further from individual property owners and ultimately in the direction of supranational government, federal control of zoning is the logical next step. Decentralization, by contrast, would be a step toward self-determination.

One of the more common arguments against local control holds that zoning cannot be left to localities because local zoning is often exclusionary. But this position is completely untenable. If a property owner finds his control over his own property limited by zoning ordinances, then his opposition is justified, because the ordinances violate his property rights. However, opposition to zoning cannot be justified simply because it’s exclusionary. After all, private property is inherently exclusionary. Hence, if zoning is opposed on the grounds that it’s exclusionary, then the concept of private property can be opposed on the same grounds. Moreover, if all neighborhoods were completely private, we could expect some neighborhoods to be more exclusive than is presently the case. Rothbard explains,

With every locale and neighborhood owned by private firms, corporations, or contractual communities, true diversity would reign, in accordance with the preferences of each community. Some neighborhoods would be ethnically or economically diverse, while others would be ethnically or economically homogeneous. Some localities would permit pornography or prostitution or drugs or abortions, others would prohibit any or all of them. The prohibitions would not be state imposed, but would simply be requirements for residence or use of some person’s or community’s land area. While statists who have the itch to impose their values on everyone else would be disappointed, every group or interest would at least have the satisfaction of living in neighborhoods of people who share its values and preferences. While neighborhood ownership would not provide Utopia or a panacea for all conflict, it would at least provide a “second-best” solution that most people might be willing to live with.

As we have seen, neighborhoods would be as exclusive or inclusive as property owners wish them to be if all neighborhoods were privately owned. Some would only allow single-family homes while others would permit duplexes and multifamily homes. It should therefore be clear that a uniform zoning code cannot represent the wishes of property owners in different locales.

In distinct contrast, one of the benefits of localism is that the wishes of property owners tend to be better represented at the local level. Astonishingly, the ostensibly libertarian Reason magazine uses this same point to argue in favor of moving zoning decisions to the state level. They approvingly quote Emily Hamilton of the Mercatus Center arguing that local policymakers are too beholden to local property owners.

Yet, localism is the better strategy here, because local regulations are more easily avoided than state regulations. If a local government’s regulations prove too onerous, it risks the loss of its most productive citizens to the next city or town. However, as a state expands the territory under its control, it becomes more difficult for citizens to escape its jurisdiction. Thus, there’s less reason for a large, centralized state to refrain from imposing such regulations.

Opposition to any and all centralization is particularly important when the centralizing measure sounds superficially appealing. This could be a supposed deregulation measure, or to use Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s examples,

It would be anti-libertarian, for instance, to appeal to the United Nations to order the breakup of a taxi-monopoly in Houston, or to the US government to order Utah to abolish its state-certification requirement for teachers, because in doing so one would have illegitimately granted these state agencies jurisdiction over property that they plainly do not own (but others do): not only Houston or Utah, but every city in the world and every state in the United States.

In our case, it is certainly true that government regulations have increased costs and limited the supply of housing. That’s not the issue. The issue is that faraway governments will predictably be even less responsive to local demands in different neighborhoods. Incidentally, it would be remiss not to mention that most who would involve the state and federal governments in local zoning are conspicuously silent on monetary policy. Yet, an inflationary monetary policy is one of the major obstacles to affordable housing.

Make no mistake: the power libertarian centralists would grant the federal government in the name of deregulation would be used in service of the broader egalitarian project. Indeed, under Biden, HUD (the Department of Housing and Urban Development) has already moved to restore an Obama-era rule which previous housing secretary Ben Carson warned would essentially turn HUD into a national zoning board. Not surprisingly, this is being sold as an attempt to reduce “racial segregation.”

Empowering state legislatures—or worse, the federal government—to abolish local regulations would be a grave mistake. Rather than limiting government, centralization under any pretext will only add new layers of government. We must therefore resist all assaults on local self-government by more distant governments and combat government regulations at the location they occur. Otherwise, distant administrators will continue to seize power and local control will become increasingly trivial.