GDP Shrinks Again as Biden Quibbles over the Definition of “Recession”

The U.S. economy contracted for the second straight quarter during the second quarter this year, the Bureau of Economic Analysis reported Thursday. With that, economic growth has hit a widely accepted benchmark for defining an economy as being in recession: two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth.

According to the BEA, the US economy contracted 0.9 percent during the second quarter in the first estimate of real GDP as a compounded annual rate. This follows the first quarter’s decline of 1.6 percent. MSNBC reports:

The decline came from a broad swath of factors, including decreases in inventories, residential and nonresidential investment, and government spending at the federal, state and local levels. Gross private domestic investment tumbled 13.5% for the three-month period

Consumer spending, as measured through personal consumption expenditures, increased just 1% for the period as inflation accelerated. Spending on services accelerated during the period by 4.1%, but that was offset by declines in nondurable goods of 5.5% and durable goods of 2.6%.

Inventories, which helped boost GDP in 2021, were a drag on growth in the second quarter, subtracting 2 percentage points from the total.

This comes just a few days after the Biden administration’s Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen attempted to preemptively head off talk of labeling the decline a recession when she declared that a second consecutive decline in GDP doesn’t really point to recession, and “we’re not in a recession” because the labor market—a lagging indicator of economic activity—is allegedly too strong.

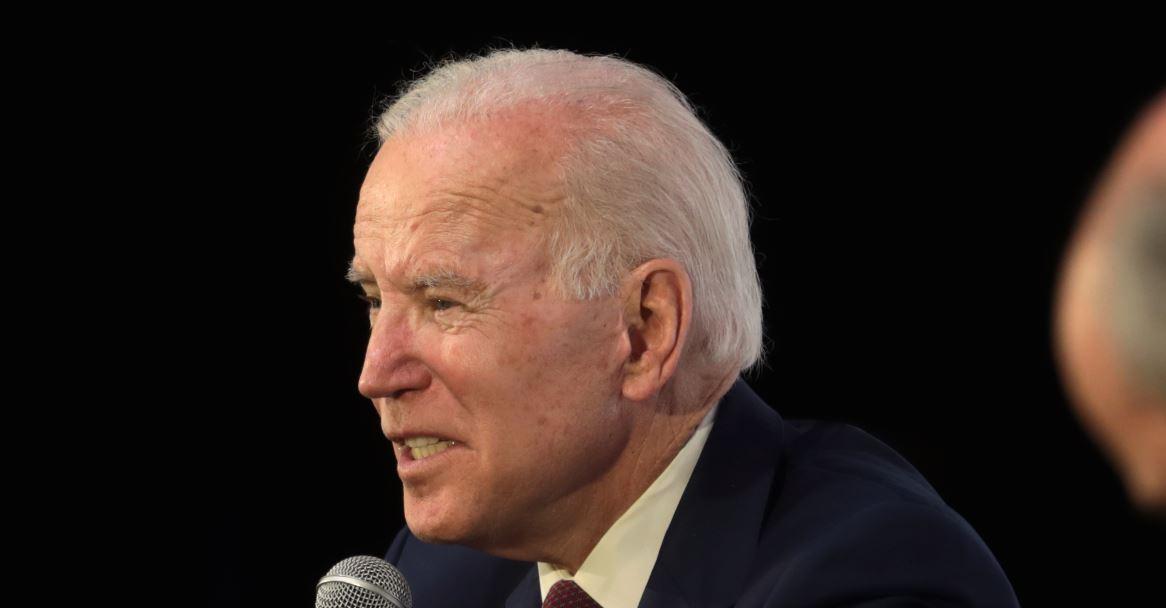

President Biden said the same on Monday. White House spokeswoman Karine Jean-Pierre continued Yellen’s PR campaign on Wednesday quibbling over the “technical” definition of a recession.

Given Thursday’s GDP numbers, however, the most appropriate answer to the question “is the US technically in a recession?” is “who cares?” The data is clear that the US economy is extremely weak and gives every impression that it’s getting weaker.

Moreover, the “technical” definition of a recession is decided by an obscure panel of eight economists—seriously, it’s eight economists from prestigious universities—who decide if the US is “technically” in recession.

Meanwhile, on the street, two quarters of declining economic growth means “the economy isn’t looking good” however one wants to slice and dice it. Or, as Rick Santelli put it Thursday morning, the two-quarters-of-negative-growth definition may not be the “technical” definition, but it is a recession “in the eyes of investors who trade in markets.” That is, for people in the real world who buy and sell things, the US is either in recession or something very close to it. Santelli concludes “call it whatever you want.”

Meanwhile, the Federal reserve and the administration are tenaciously clinging for dear life to the job numbers as evidence that the economy is doing too well to be called a recession. Perhaps. But the job numbers are nothing to crow about and point toward more weakening themselves. When we look at real wages, the news is anything but great. Specifically, both Fed chair Powell and Sec. Yellen have repeatedly pointed to the nonfarm total employment numbers, and the JOLTS data showing a healthy supply of job openings. But this is only a small slice of the story.

For example, there are two surveys of employment, and only the “establishment” survey of large businesses shows job gains. The household survey, on the other hand, shows jobs have gone nowhere for months, and have even declined slightly (month-over-month) for two of the past three months. The establishment survey is a survey of jobs. The household survey is a survey of employed persons. The fact that the former is growing while the latter isn’t suggests people are taking on second jobs to deal with price inflation, but that more people aren’t actually becoming employed.

This would make sense given that real wages have fallen below the trend. Looking at median weekly real earnings, we find that incomes are falling. That’s not exactly evidence the economy is too strong to be in recession.

The initial unemployment data is troubling as well. The post-covid downward trend in newly jobless ended back in March. As Danielle Dimartino Booth put it on Wednesday

All signs point to an economy in recession. Most importantly, U.S. jobless claims have risen more than 50% since their mid-March lows surpassing a threshold associated with recession in cycles back to 1968.

Other indicators often look even more grim. The yield curve points to recession. The small business index—which goes back 50 years, just hit a record low. The Chicago Fed’s National Activity Index shows two months below trend—which points to recession.

So, will the NBER’s little board of economists conclude the US was “technically” in recession in mid 2022 when it issues its opinion months from now? It doesn’t really matter when it comes to making a judgment about the state of the economy right now. The state of the economy is not good. Powell knows it. Yellen knows it. Biden—assuming he still has the cognitive ability to comprehend such things—probably knows it too.

This is the economy given to us by the Fed and by the past two administrations working together to fuel record-breaking budgets and deficits and money-printing never before seen in peacetime. This is the natural outcome of the easy-money fueled Trump boom of 2018 and 2019 during which Trump repeatedly howled at Powell to keep the printing presses going. Powell happily complied even though any reasonable Fed chairman would have interpreted the relatively strong economic indicators of that period as a reason to finally end QE and stop forcing down interest rates. Powell—being the new Arthur Burns—kept the money spigot open. Then came covid and Trump’s populist spend-everything-everywhere policy turned $800 billion deficits into $3 trillion deficits. Biden merely continued the binge. Under these conditions, ultra-low interest rates and central bank Treasury purchases became indispensable in keeping government debt payments from going into the stratosphere.

Through it all, most mainstream economists assured us price inflation would be no big deal and would—at worst—be “transitory.” They were so wrong that even the relentlessly obtuse Paul Krugman had to admit he was wrong. As is usual with their little grift, the professional economists claimed no one could predict that price inflation would result from trillions of dollars of helicopter money. It was all a surprise to them. Nor should we assume this is the end of the bad news. For example, by late 2007, the US economic data was already looking “not good.” But few would claim the US was headed into a serious recession. That only became undeniable many months later. Are we now headed into a similar situation? It’s impossible to say much with certainly. But one thing we know for sure: the professional economists and the technocrats don’t know either.