Rothbard on Gold

What would people use for money in a genuine free market? A lot of people answer the question in this way. We really don’t know the answer for sure. It would be up to the people who live in that society. Because in a genuine free market, there would be no state at all, there would be no money mandated by the state. People would compete to establish the money they liked best. Maybe people would settle on a gold or silver standard, as they had done in the past. But maybe they wouldn’t. They might prefer electronic currency like bitcoin. Or maybe there would be all sorts of different monies, with no clear winner.

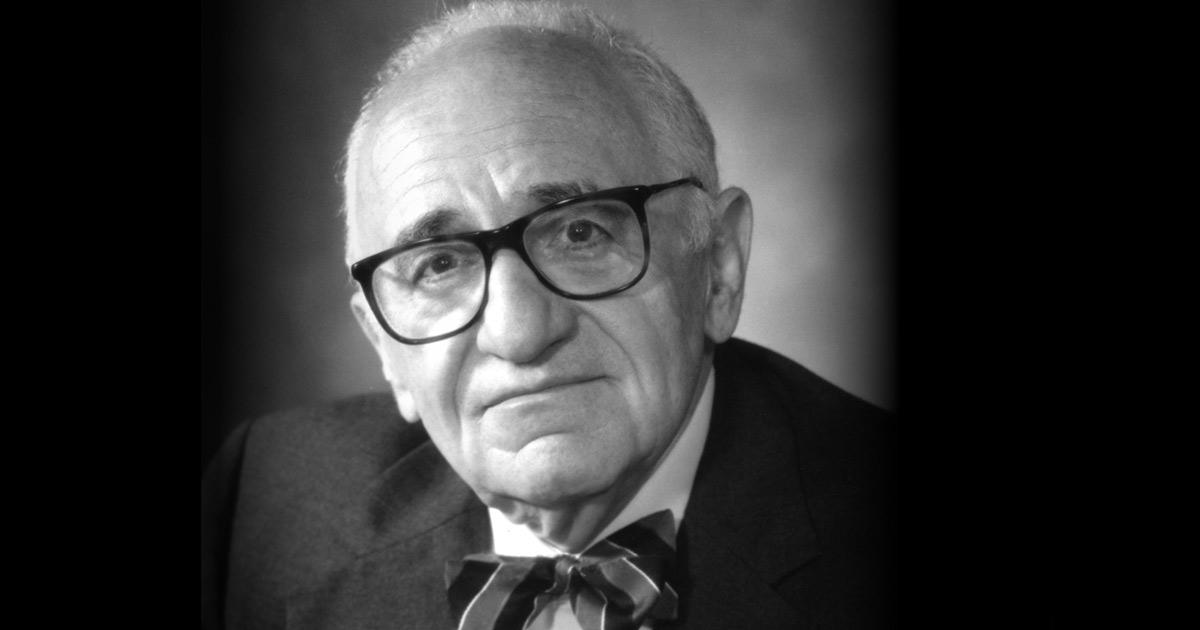

Murray Rothbard doesn’t agree with this. He was aware of competitive money, because F.A. Hayek had suggested it. People have the right to offer competing monies, as Hayek advocated. But Murray thought they would be unlikely to do this. The competition had already taken place, and precious metals were the winner. Why go through the same process again? As Murray explains in his great article, “The Case for a Genuine Gold Dollar”:

“In recent years an increasing number of economists have understandably become disillusioned by the inflationary record of fiat currencies. They have therefore concluded that leaving the government and its central bank power to fine tune the money supply, but abjuring them to use that power wisely in accordance with various rules, is simply leaving the fox in charge of the proverbial henhouse. They have come to the conclusion that only radical measures can remedy the problem, in essence the problem of the inherent tendency of government to inflate a money supply that it monopolizes and creates. That remedy is no less than the strict separation of money and its supply from the state.

The best known proposal to separate money from the state is that of F.A. Hayek and his followers. Hayek’s ‘denationalization of money’ would eliminate legal tender laws, and allow every individual and organization to issue its own currency, as paper tickets with its own names and marks attached. The central government would retain its monopoly over the dollar, or franc, but other institutions would be allowed to compete in the money creation business by offering their own brand name currencies. Thus, Hayek would be able to print Hayeks, the present author to issue Rothbards, and so on. Mixed in with Hayek’s suggested legal change is an entrepreneurial scheme by which a Hayek-inspired bank would issue ‘ducats,’ which would be issued in such a way as to keep prices in terms’ of ducats constant. Hayek is confident that his ducat would easily out-compete the inflated dollar, pound, mark, or whatever.

Hayek’s plan would have merit if the thing—the commodity—we call ‘money’ were similar to all other goods and services. One way, for example, to get rid of the inefficient, backward, and sometimes despotic U.S. Postal Service is simply to abolish it; but other free market advocates propose the less radical plan of keeping the post office intact but allowing any and all organizations to compete with it. These economists are confident that private firms would soon be able to outcompete the post office. In the past decade, economists have become more sympathetic to deregulation and free competition, so that superficially denationalizing or allowing free competition in currencies would seem viable in analogy with postal services or fire-fighting or private schools.

There is a crucial difference, however, between money and all other goods and services. All other goods, whether they be postal service or candy bars or personal computers, are desired for their own sake, for the utility and value that they yield to consumers. Consumers are therefore able to weigh these utilities against one another on their own personal scales of value. Money, however, is desired not for its own sake, but precisely because it already functions as money, so that everyone is confident that the money commodity will be readily accepted by any and all in exchange. People eagerly accept paper tickets marked ‘dollars’ not for their aesthetic value, but because they are sure that they will be able to sell those tickets for the goods and services they desire. They can only be sure in that way when the particular name, ‘dollar,’ is already in use as money.

Hayek is surely correct that a free market economy and a devotion to the right of private property requires that everyone be permitted to issue whatever proposed currency names and tickets they wish. Hayek should be free to issue Hayeks or ducats, and I to issue Rothbards or whatever. But issuance and acceptance are two very different matters. No one will accept new currency tickets, as they well might new postal organizations or new computers. These names will not be chosen as currencies precisely because they have not been used as money, or for any other purpose, before.

Hayek and his followers have failed completely to absorb the lesson of Ludwig von Mises’ ‘regression theorem,’ one of the most important theorems in monetary economics. Mises showed, as far back as 1912, that since no one will accept any entity as money unless it had been demanded and exchanged earlier, we must therefore logically go back (regress) to the first day when a commodity became used as money, a medium of exchange. Since by definition the commodity could not have been used as money before that first day, it could only be demanded because it had been used as a nonmonetary commodity, and therefore had a preexisting price, even in the era before it began to be used as a medium. In other words, for any commodity to become used as money, it must have originated as a commodity valued for some nonmonetary purpose, so that it had a stable demand and price before it began to be used as a medium of exchange. In short, money cannot be created out of thin air, by social contract, or by issuing paper tickets with new names on them. Money has to originate as a valuable nonmonetary commodity. In practice, precious metals such as gold or silver, metals in stable and high demand per unit weight, have won out over all other commodities as moneys. Hence, Mises’ regression theorem demonstrates that money must originate as a useful nonmonetary commodity on the free market.

But one crucial problem with the Hayekian ducat is that no one will take it. New names on tickets cannot hope to compete with dollars or pounds which originated as units of weight of gold or silver and have now been used for centuries on the market as the currency unit, the medium of exchange, and the instrument of monetary calculation and reckoning.

Hayek’s plan for the denationalization of money is Utopian in the worst sense: not because it is radical, but because it would not and could not work. Print different names on paper all one wishes, and these new tickets still would not be accepted or function as money; the dollar (or pound or mark) would still reign unchecked. Even the removal of the legal tender privilege would not work, for the new names would not have emerged out of useful commodities on the free market, as the regression theorem demonstrates they must. And since the government’s own currency, the dollar and the like, would continue to reign unchallenged as money, money would not have been denationalized at all. Money would still be nationalized and a creature of the state; there would still be no separation of money and the state. In short, even though hopelessly Utopian, the Hayek plan would scarcely be radical enough, since the current inflationary and state-run system would be left intact.

Even the variant on Hayek whereby private citizens or firms issue gold coins denominated in grams or ounces would not work, and this is true even though the dollar and other fiat currencies originated centuries ago as names of units of weight of gold or silver. Americans have been used to using and reckoning in dollars for two centuries, and they will cling to the dollar for the foreseeable future. They will simply not shift away from the dollar to the gold ounce or gram as a currency unit. People will cling doggedly to their customary names for currency; even during runaway inflation and virtual destruction of the currency, the German people clung to the mark in 1923 and the Chinese to the ‘yen’ in the 1940s. Even drastic revaluations of the runaway currencies which helped end the inflation kept the original ‘mark’ or other currency name.

Hayek brings up historical examples where more than one currency circulated in the same geographic area at the same time, but none of the examples is relevant to his ‘ducat’ plan. Border regions may accept two governmental currencies. But each has legal tender power, and each had been in lengthy use within its own nation. Multicurrency circulation, then, is not relevant to the idea of one or more new private paper currencies. In addition, Hayek might have mentioned the fact that in the United States, until the practice was outlawed in 1857, foreign gold and silver coins as well as private gold coins, circulated as money side by side with official coins. The fact that the Spanish silver dollar had long circulated in America along with Austrian and English specie coins, permitted the new United States to change over easily from pound to dollar reckoning. But again, this situation is not relevant, because all these coins were different weights of gold and silver, and none was fiat government money. It was easy, then, for people to refer the various values of the coins back to their gold or silver weights. Gold and silver had of course long circulated as money, and the pound sterling or dollar were simply different weights of one or the other metals. Hayek’s plan is a very different one: the issue of private paper tickets marked by new names and in the hope that they are accepted as money.

If people love and will cling to their dollars or francs, then there is only one way to separate money from the state, to truly denationalize a nation’s money. And that is to denationalize the dollar (or the mark or franc) itself. Only privatization of the dollar can end the government’s inflationary dominance of the nation’s money supply.”

If competition in money isn’t the way to go, how do we get to free market money? As usual Murray has the answer:

“We conclude, then, that the dollar must be redefined in terms of a single commodity, rather than in terms of an artificial market basket of two or more commodities. Which commodity, then, should be chosen? In the first place, precious metals, gold and silver, have always been preferred to all other commodities as mediums of exchange where they have been available. It is no accident that this has been the invariable success story of precious metals, which can be partly explained by their superior stable nonmonetary demand, their high value per unit weight, durability, divisibility cognizability, and the other virtues described at length in the first chapter of all money and banking textbooks published before the U.S. government abandoned the gold standard in 1933. Which metal should be the standard, then, silver or gold? There is, indeed, a case for silver, but the weight of argument holds with a return to gold. Silver’s increasing relative abundance of supply has depreciated its value badly in terms of gold, and it has not been used as a general monetary metal since the nineteenth century. Gold was the monetary standard in most countries until 1914, or even until the 1930s. Furthermore, gold was the standard when the U.S. government in 1933 confiscated the gold of all American citizens and abandoned gold redeemability of the dollar, supposedly only for the duration of the depression emergency. Still further, gold and not silver is still considered a monetary metal everywhere, and governments and their central banks have managed to amass an enormous amount of gold not now in use, but which again could be used as a standard for the dollar, pound, or mark.

This brings up an important corollary. The United States, and other governments, have in effect nationalized gold. Even now, when private citizens are allowed to own gold, the great bulk of that metal continues to be sequestered in the vaults of the central banks. If the dollar is redefined in terms of gold, gold as well as the dollar can be jointly denationalized. But if the dollar is not defined as a weight of gold, then how can a denationalization of gold ever take place? Selling the gold stock would be unsatisfactory, since this (1) would imply that the government is entitled to the receipts from the sale and (2) would leave the dollar under the absolute fiat control of the government.

It is important to realize what a definition of the dollar in terms of gold would entail. The definition must be real and effective rather than nominal. Thus, the U.S. statutes define the dollar as 1/42.22 gold ounce, but this definition is a mere formalistic accounting device. To be real, the definition of the dollar as a unit of weight of gold must imply that the dollar is interchangeable and therefore redeemable by its issuer in that weight, that the dollar is a demand claim for that weight in gold.

Furthermore, once selected, the definition, whatever it is, must be fixed permanently. Once chosen, there is no more excuse for changing definitions than there is for altering the length of a standard yard or the weight of a standard pound.

Before proceeding to investigate what the new definition or weight of the dollar should be, let us consider some objections to the very idea of the government setting a new definition. One criticism holds it to be fundamentally statist and a violation of the free market for the government, rather than the market, to be responsible for fixing a new definition of the dollar in terms of gold. The problem, however, is that we are now tackling the problem in midstream, after the government has taken the dollar off gold, virtually nationalized the stock of gold, and issued dollars for decades as arbitrary and fiat money. Since government has monopolized issue of the dollar, and confiscated the public’s gold, only government can solve the problem by jointly denationalizing gold and the dollar. Objection to government’s redefining and privatizing gold is equivalent to complaining about the government’s repealing its own price controls because repeal would constitute a governmental rather than private action. A similar charge could be leveled at government’s denationalizing any product or operation. It is not advocating statism to call for the government’s repeal of its own interventions.

A corollary criticism, and a favorite of monetarists, asks why gold standard advocates would have the government ‘fix the (dollar) price of gold’ when they are generally opposed to fixing any other prices. Why leave the market free to determine all prices except the price of gold?

But this criticism totally misconceives the meaning of the concept of price. A ‘price’ is the quantity exchanged of one commodity on the market in terms of another. Thus, in barter, if a package of six light bulbs is exchanged on the market for one pound of butter, then the price per light bulb is one-sixth of a pound of butter. Or, if there is monetary exchange, the price of each light bulb will be a certain weight of gold, or, these days, numbers of cents or dollars. The important point is that price is the ratio of quantities of two commodities being exchanged. But if money is on a gold standard, the dollar and gold will no longer be two independent commodities, whose price should be free to fluctuate on the market. They will be one commodity, one a unit of weight of the other. To call for a ‘free market’ in the ‘price of gold’ is as ludicrous as calling for a free market of ounces in terms of pounds, or inches in terms of yards. How many inches equal a yard is not something subject to daily fluctuations on the free or any other market. The answer is fixed eternally by definition, and what a gold standard entails is a fixed, absolute, unchanging definition as in the case of any other measure or unit of weight. The market necessarily exchanges two different commodities rather than one commodity for itself. To call for a free market in the price of gold would, in short, be as absurd as calling for a fluctuating market price for dollars in terms of cents. How many cents constitute a dollar is no more subject to daily fluctuation and uncertainty than inches in terms of yards. On the contrary, a truly free market in money will exist only when the dollar is once again strictly defined and therefore redeemable in terms of weights of gold. After that, gold will be exchangeable, at freely fluctuating prices, for the weights of all other goods and services on the market.

In short, the very description of a gold standard as ‘fixing the price of gold’ is a grave misinterpretation. In a gold standard, the ‘price of gold’ is not unaccountably fixed by government intervention. Rather, the ‘dollar,’ for the past half-century a mere paper ticket issued by the government, will become defined once again as a unit of weight of gold.”

As usual, Murray is right. We should for a return to the gold standard, not waste time with space cadet fantasies about new kinds of money.