Boom to Bust: How Inflation Turns into Deflation

In order to understand the effects of inflation it is helpful to understand that inflation is not a general rise in prices as such, but an increase in the supply of money which then sets in motion a general increase in the prices of goods and services in terms of money.

Consider the case of a fixed stock of money. Whenever people increase their demand for some goods and services, money is going to be allocated toward these goods and services. In response, the prices of these goods and services are likely to increase—more money will be spent on them.

Since we have an unchanged stock of money, less money can now be allocated toward other goods and services. Given that the price of a good is the amount of money spent on the good, this means that the prices of other goods will decline, i.e., less money will be spent on them.

In order for there to be a general rise in prices, there must be an increase in the money stock. With more money and no change in the money demand, people can now allocate a greater amount of money toward all goods and services.

According to Mises in Economic Freedom and Interventionism,

Inflation, as this term was always used everywhere and especially in this country, means increasing the quantity of money and bank notes in circulation and the quantity of bank deposits subject to check. But people today use the term “inflation” to refer to the phenomenon that is an inevitable consequence of inflation, that is the tendency of all prices and wage rates to rise. The result of this deplorable confusion is that there is no term left to signify the cause of this rise in prices and wages. There is no longer any word available to signify the phenomenon that has been, up to now, called inflation. (p. 99)

Inflation is a process in which the last recipients of newly created fiat money are impoverished while the early recipients of this money are enriched. This process of impoverishment is set in motion as a result of an increase in the money supply.

This increase activates an exchange of nothing for something. This amounts to the diversion of real savings from the last recipients of the newly generated money to the early recipients.

Now, if the growth rate of money supply stands at 10 percent while the growth rate of the production of goods and services also stands at 10 percent, the prices of these goods and services on average will increase by 0 percent. In popular thinking, this will be seen as if there is no inflation here.

However, knowing that inflation is an increase in money supply, it’s clear that the rate of inflation is 10 percent. What matters here is not changes in the prices of goods and services but the increase in money supply. This increase sets the process of impoverishment in motion.

How Much Inflation Is There?

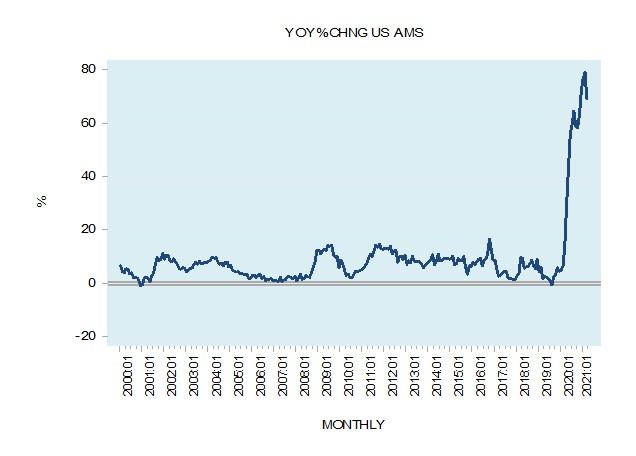

So what is the present status of inflation? By popular thinking, represented by the yearly growth rate in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), inflation stood at 2.6 percent in March, against 1.7 percent in February and 1.5 percent in March 2020. However, in terms of money supply, the growth rate of inflation stood at 69.2 percent in March against 13.4 percent in March 2020. Massive monetary increases have weakened the process of real savings formation. As a result, businesses’ ability to grow the economy has been severely impaired.

Moreover, the ability of businesses to grow the economy has weakened further because of massive government spending, which has diverted real savings from businesses toward various nonproductive government projects. Note that government spending is only likely to strengthen in the near term. Because of this massive fiscal and monetary spending, the pool of real savings—the heart of economic growth—could be in serious trouble.

Thus, a likely decline in the pool of real savings is expected to significantly weaken economic activity ahead; subsequently, the quality of banks’ assets will likely deteriorate. Therefore, the yearly growth rate of banks’ inflationary credit, or lending out of “thin air,” is poised to weaken visibly, thus putting pressure on the growth rate of money supply. This happens because as bank assets decline in quality, and as potential borrowers decline in value, banks lend less and put downward pressure on the money supply.

Note that the yearly growth rate of money supply has already eased to 69.2 percent in March from 79.1 percent the month before. In the midst of a financial bubble—as we likely are now—even a slight softening in the growth rate of money supply could be fatal.

Note: this graph shows changes in the TMS money supply measure.

This is because bubble activities cannot stand on their own feet; they require support from increases in money supply that divert to them real savings from wealth generators. Also, note again that a major cause behind the possible decline in the pool of real savings is unprecedented increases in money supply and massive government spending. While the pool of real savings is still growing, the massive money supply increase is likely to be followed by an upward trend in the growth rate of the prices of goods and services. This could start early next year. Once the pool of real savings starts to decline, however—because of massive monetary pumping and reckless fiscal policies—various bubble activities are will plunge. This, in turn, is likely to result in a large decline in economic activity and in the money supply.

Ironically, although money supply growth is immense right now, as a result of the possible burst of bubble activities the prices of goods and services could actually decline in coming years. That is, deflation will come as industry bubbles pop. This could occur as early as the second half of 2022. Yet the possibility of deflation hinges on whether the pool of real savings is declining, and this is notoriously difficult to observe.