The Crime of ’71: When Nixon Ended the Dollar’s Last Connection to Gold

Almost fifty years ago, on August 15, 1971, the US administration under President Richard Nixon (1913–94) abolished the gold redeemability of the US dollar. It was through this unilateral decision that the world’s major currencies were turned into irredeemable money: money that is no longer backed by physical gold. This surprise coup put an end to the system of Bretton Woods, which had been adopted in 1944.

From July 1 to 22 of that year, 730 delegates from forty-four nations met in the village of Bretton Woods in the US state of New Hampshire to determine the global monetary order for the period after the Second World War. Here it was agreed to give the US dollar the status of the world reserve currency. Thirty-five US dollars corresponded to one troy ounce of gold (i.e., 31.10347 … grams). All other currencies (the French franc, British pound, Swiss franc, etc.) were linked to the greenback at a fixed exchange rate, and they could be converted into greenbacks at any time. In this way they too were—at least indirectly—tied to physical gold.

However, one should not think that the Bretton Woods system was something like a reestablishment of the gold standard. Not even close. At best, it was something of a pseudo–gold standard. Although the US dollar was defined in terms of its physical gold weight, gold no longer circulated in day-to-day business in the world’s major economies. In the US, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945) in 1933 had made gold ownership illegal for American citizens. Banks and consumers had to hand over their gold to the US Treasury. In return, they received US dollar banknotes and balances at the US central bank. Only in international payment transactions between central banks was the US dollar still redeemable in gold.

At the conference of Bretton Woods there was a consensus that there could be no reliable world currency system without gold playing a role. The proposals for the design of the world monetary system which competed at the conference—the so-called Keynes Plan and the White Plan—all assigned an anchor function to gold. The yellow metal was seen as a kind of perfect money; at least no one could say how something better could be substituted for it.

At the end of the day, however, only a “dollar currency standard” was agreed upon at Bretton Woods. That is, the world relied on the promise given by the US that it would exchange the US dollar in full for physical gold upon request. Not a good decision, it would turn out. But at first the Bretton Woods system worked reasonably—despite a number of structural shortcomings. The economies around the world recovered; world trade and world capital movements expanded.

Soon, however, dark clouds gathered. As early as the 1950s, the US began to get bogged down in an increasingly bellicose foreign policy. They financed the costs of the Korean and Vietnam Wars mainly by spending new US dollars not backed by physical gold. As expected, goods price inflation began to take off. The purchasing power of the US dollar declined noticeably, and with it confidence in the world reserve currency declined. More and more nations began to demand their US dollars holdings converted into physical gold.

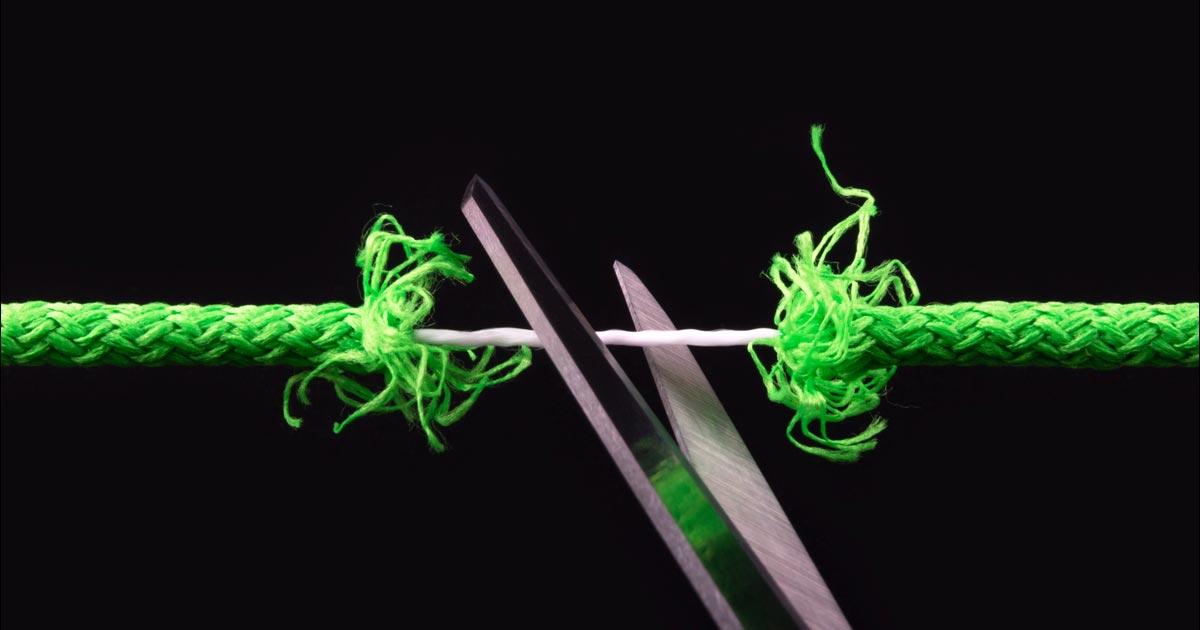

The American gold reserve—at that time it amounted to about two-thirds of the world’s monetary gold—melted like snow in the sun. The US was threatened with insolvency in terms of gold payments. And this is why President Nixon pulled the emergency brake in the summer of 1971 and decided not to redeem the US dollar in gold anymore—as had been contractually agreed upon. The decision to end the gold redeemability of the greenback was probably the largest act of monetary expropriation of modern times.

The monetary system of the world was fundamentally changed in one fell swoop. In fact, all currencies became nonredeemable paper money, or “fiat money,” money that can be increased by any amount deemed politically desirable at any moment in time. The preferred method of producing new fiat money is through credit expansion on the part of central banks and commercial banks. Unsurprisingly, chronic price inflation comes with fiat money: the phenomenon where the prices of goods and services keep rising over time.

What is more, the issuing of fiat money through bank lending causes recurring waves of speculation, bubbles, and financial and economic crises. Most notorious are the so-called boom and bust cycles: in an effort to keep expanding the fiat money supply, central banks artificially suppress market interest rates, thereby inducing a pseudo-upswing (“boom”), which sooner or later has to end in a recession (“bust”). And since during a cycle debt typically swells faster than economic performance increases, the overall debt pyramid keeps growing and becomes overwhelming over time.

Furthermore, fiat money makes the state bigger and more powerful. The state’s central bank provides it with any desired amount of money created out of thin air on credit, provided at most favorable funding costs. As a result, the state can literally buy anything and expand its power; it can most conveniently grow out the welfare and warfare state. The state’s expansion inevitably comes at the expense of the freedoms of citizens and entrepreneurs.

That said, the move away from gold money some fifty years ago has had very far-reaching consequences for Western economies and societies. It was instrumental in undermining and pushing back the free economic and societal order, replacing it with state interventionism and state planning. On top of that, things are likely to take dramatic turn, as the fiat money system seems to be about to reach its limits.

Following the politically dictated lockdown crisis in 2020/21, global debt has reached alarming record levels. The International Institute of Finance (IIF) estimates that at the end of the first quarter of 2021, global debt stood at $289 trillion, or 360 percent of global economic output. Looked at soberly, it is a mountain of debt that no one can or will repay.

The world’s major central banks have reduced market interest rates to or even below zero, and keep the electronic printing presses running for financing struggling states and banks through the issuance of huge amounts of newly created fiat money. In other words, policymakers have unabashedly resorted to inflation to keep the system afloat. As experience shows, inflation all too easily begets more inflation, which could in the extreme prove to be self-destructive for the world’s fiat money system.

If the fiat monetary system is to be saved from collapse, the economies will unfortunately have to throw overboard what little is left of the free economic and social system, for basically all the remaining corrective forces of the free market will have to be put to rest. In fact, governments will have to take recourse to more regulation, prohibitions, taxes, controls etc. In other words, the free economic and societal system will fall victim to the effort of preserving the fiat money system.

Seen in this way, the move away from gold money, which reached its dramatic end point in the summer of 1971, was much more than just historical occurrence well in the past. It is was a rather fateful event, the final nail in the coffin of the idea of sound money; we may even speak of the “crime of 1971.” It actually can also be seen as a kind of Mephistophelian trade: good gold money was exchanged for bad fiat money—as in the Faustian bargain, supreme moral values, or the personal soul, were surrendered to an evil spirit. In any case, the decoupling of money from gold and the entrusting of the money-producing enterprise to the state and its central bank henceforth will probably prove to be one of the greatest follies in human history.