Self-Interest versus Racial Solidarity

Modern-day race theories—much like the standard racist theories of the past—assume that racial solidarity ought to be the overriding factor in all human behavior. Whites are supposed to always ally with whites. Meanwhile, blacks are supposed to always side with other blacks, even if this means abandoning self-interest. Experience suggests, however, that blacks are not simply automatons who always choose notions of racial unity over self-interest.

In other words, it seems race relations are more complex than modern race baiters and traditional racists would have us believe.

We can find some examples of these complex relationships in the so-called maroon communities of Jamaica and North America.

The Case of the Jamaican Maroons

After the British conquered Jamaica in 1655, the ex-slaves of the Spanish refused to become their subjects by opting to create autonomous communities in the country’s interior. These individuals became known as the maroons. To the surprise of the British, the maroons proved to be formidable warriors, and as a result, the British had to sue for peace. So, to stem resistance, the British concluded a treaty with the Leeward Maroons in 1738, before gaining the cooperation of the Windward Maroons in 1739. Per their agreement with the British, the maroons were required to police fugitive slaves, and they executed this duty with great vigor.

In exchange for their commitment to not contesting white hegemony, these former slaves were rewarded with money, clothes, guns, and cattle. For instance, with the assistance of the maroons, planters were able to squash the 1760 revolt orchestrated by Chief Tacky, an Akan slave. Tacky was actually killed by the maroon Captain Davy of Scotts Hall. As trusted associates, the maroons would prove to be useful in quelling future insurrections, according to Michael Gomez: “The Leeward and Windwards … in compliance with the 1739 treaty, fought alongside the planters … to end the revolts of 1761, 1765, and 1766, all Akan-led conspiracies betrayed by informants. The Leewards, particularly the Accompong and Trelawny Town groups were rewarded with twice as much money as were the Windward groups of Scotts Hall, Moore Town, and Charles Town whose participation was considerably less enthusiastic.”

Planters also employed the services of the maroons to capture runaways. They were so efficient that some writers contend that the maroons acted as a police force. Helen Mckee writes:

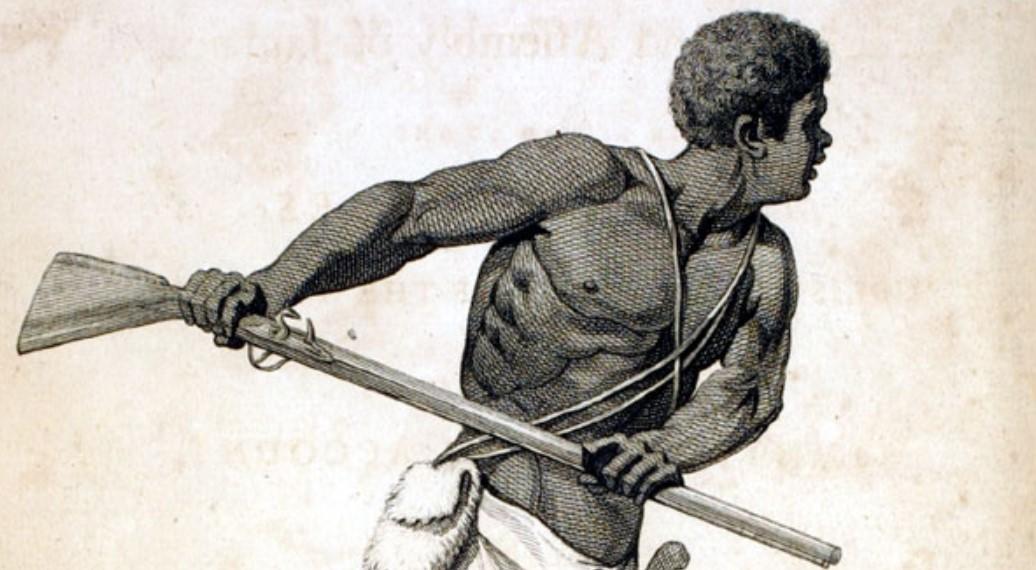

Following Tacky’s Rebellion, maroons were employed to hunt runaways so extensively by white Jamaicans that the maroons came to be used almost as a police force. In 1763, Cudjoe’s men chased 11 runaways, killed three and took the rest who were tried at Savanna-la-Mar. Some of the runaways were hanged and others burnt alive “by a slow fire behind the Court House” because they allegedly confessed to the murders of a Mr. Wright and Mr. Grizzle at Round Hill in Hanover. Further examples of maroons hunting runaways in the eighteenth century can be found throughout the archives. However, white settlers were not just reliant on the maroons’ martial assistance; on occasion, maroons were even said to provide them with information on slave runaways or uprisings. [Thomas] Thistlewood claimed that, long before one small rebellion, Colonel Cudjoe “wrote to Col. Barclay & the Gentlemen of this parish … to warn them of this that has happened.” The relationship between some planters and maroons seems to have gone beyond employment to one of providing intelligence on the enslaved population. In the process of uniting under a maroon identity, it seems clear that maroons were aligning themselves closest to local whites. Indeed, when Three Fingered Jack threatened the colony between 1780 and 1781, it was a maroon who captured and killed him, eventually claiming £200 as a reward.

Again in 1819, the maroons demonstrated their commitment to the plantocracy by destroying a settlement built by fugitive slaves in the hills of Hellshire.

What is even more intriguing is that in 1795, due to longstanding grievances, the Trelawny Town Maroons waged war against the plantocracy but failed to generate the support of Accompong Town Maroons, who sided with the planters, while the eastern maroons remained neutral. After a smashing defeat, these maroons were deported to Nova Scotia. The maroons stayed in Nova Scotia for a short period, until they were sent to Sierra Leone, where they continued their role as reliable defenders of the British Empire. Ruma Chopra comments on the royalist tradition of the maroons in Sierre Leone:

The maroons—with their reputation for tenacity and bravery and their knowledge of guerilla tactics—met the empire’s immediate military needs in Sierra Leone. As they had protected the slaveholders from slave rebels in Jamaica, for decades, the maroons would protect the Sierra Leone’s government from black loyalists. At once, the maroon leaders inserted themselves as effective mediators: whites in Sierra Leone could trust them to reassert the king’s authority. As Colonel James Montague, the maroon leader, explained: “They like King George and white man well—if them settler don’t like King George nor this Government—only let Maroon see them”. Voluntary military service was a public affirmation of loyalism.

Slaves Pursued Self-Interest, Even with Limited Options

To the maroons, cooperating with the British was a better gamble than aiding blacks, because they were sure of the benefits that could be derived from alliances with whites. Likewise, in America blacks sought to cultivate partnerships with white oppressors at the expense of their fellow blacks. However, in the American South, there was a reverse relationship: instead, black slaves assisted white planters to undermine the North American maroons. Although planters certainly applied a number of coercive measures to intimidate slaves into cooperation, historians Tim Lockley and David Doddington dispute the narrative that slaves were rarely motivated by self-interest:

It is apparent that some slaves actively desired to ingratiate themselves with whites. It was most likely the prospects of financial reward that led two slaves, Tom and Jack, to “brave every hazard” in order to bring about the apprehension of one of “a gang of lawless and desperate runaways” near Georgetown.

As expected, the legislature of South Carolina compensated Tom and Jack; however, the fugitive was executed.

Moreover, when maroons raided plantations, they depleted supplies, thereby reducing the distribution of food available to slaves. Further, to minimize losses, planters would resort to limiting allowances of clothing for the enslaved population. In truth, the maroons were indiscriminate in targeting the residents of plantations, and black slaves were hurt in the process. Lockley and Doddington submit that slaves were justified in their contempt for maroons:

Due to their militaristic structure, maroon communities were more capable than individual runaways of making daring armed raids on plantations, and these inevitably led to the risk of injury to slaves…. The use of buckshot meant that a well-aimed blast from a firearm could accidentally maim or even kill an innocent slave, and sometimes lethal violence could be used deliberately—shared oppression was not sufficient to spare slaves from maroon violence.

The maroons were even notorious for robbing slaves. Hence by their unscrupulous actions they alienated slaves, thus further undermining racial solidarity.

In spite of what some ethnic nationalists may prefer, race is not always a unifying factor in combatting oppression from outside groups. In the battle to attain power and defend one’s interests, smaller, localized group interests will often trump more abstract notions of race. Many individuals may come to their own conclusions about what is best for themselves and their close associates, even if today’s race theorists in retrospect may deem these calculations to be “wrong.”