Why the US Supports Secession for Africans, but Not for Americans

The twentieth century was a century of secession. Since the end of the Second World War, the number of independent states in the world has nearly tripled as new states, through acts of secession, came into existence. This was driven largely by the wave of decolonization that occurred following the Second World War.1

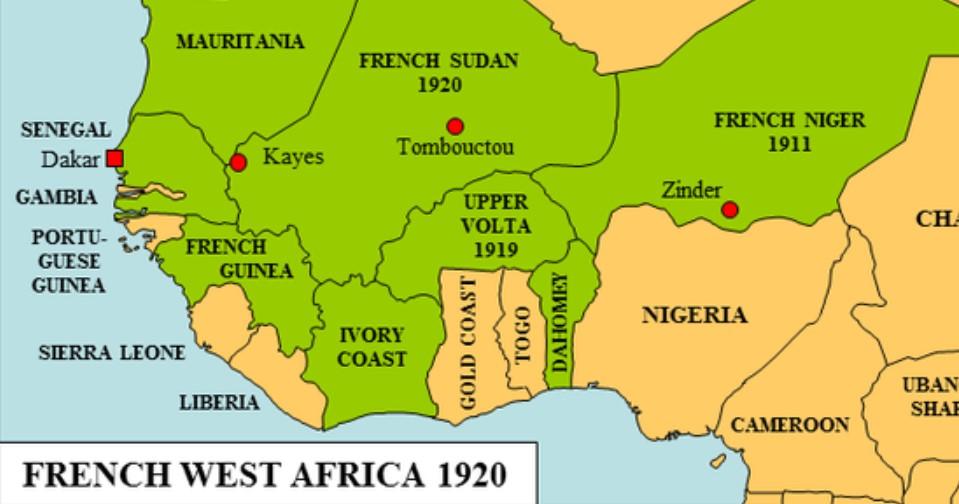

From the late 1940s through the 1970s, across Africa and Asia—and even in Europe, as in the case of Malta—dozens of colonial territories declared independence through referenda and other strategies.

Throughout these processes of decolonization, much of the international community—including the United States—was supportive. Following the Second World War, the United States explicitly supported decolonization efforts, and was often quick to recognize the new countries’ sovereignty and establish diplomatic relations.

The US frequently supported these acts of secession because, it was said, it was morally imperative so as to respect the rights of “self-determination” denied to the world’s colonized territories. Moreover, many of the world’s sovereign states supported this global spree of secessionist movements, from the US, to the Soviet Union and China, and within many international organizations like the United Nations.

Yet, when secession is suggested in other contexts, today’s regimes are far less enthusiastic and generally condemn the very idea of secession.

For example, the Spanish regime today opposes independence for Catalonia and for the Basque Country. The Russians fought a long and bloody war to prevent independence for Chechnya. The US regime would clearly take a very dim view of any member state or region that attempted to declare independence.

Doesn’t this illustrate a glaring inconsistency in thinking? If self-determination is desirable for African or Asian colonies, why is secession verboten in other situations?

The answer is it’s easy to support secession in far-off territories of little strategic value. When secession hits “close to home,” on the other hand, regimes that have long pretended to be in favor of self-determination will quickly turn on a dime and begin to manufacture a multitude of reasons as to why secession and self-determination are not, in fact, tolerable after all.

Defining down the Meaning of “Colony”

The idea of national self-determination as an explicit political movement originates with the American Revolution. As Jefferson and his colleagues stated in the Declaration of Independence, “it is the right of the people to alter or abolish” a government deemed to be abusive by the governed. Obviously—given that the Declaration of Independence was a declaration of secession—these strategies rightfully employed by “the people” included secession.

It is easy to apply the Jefferson’s notion of self-determination to any colony, whether in North America in the eighteenth century, or in Africa in the twentieth. Thus, governments looking to show off their humanitarian chops—what we might today call “virtue signaling”—will embrace secession. But only for purposes of decolonization—and regimes are very careful to limit what they mean by “colonies” and “decolonization.”

In this way of thinking, there’s a bright shiny line between a population oppressed by colonizers, and one that isn’t. Cases like Nigeria or India, for example, offer easy cases. Nigeria and India were both controlled by Britain and subject to British political domination. But, both these places are far away from Britain itself, and their populations—at least in the mid twentieth century—were easy to distinguish visually from the British population. In other words, the people in these colonies “looked like” what one expects to see in foreigners exploited by colonizers. Moreover, these populations did not have direct representation in Parliament.

Yet none of these factors are really the key issues in determining if a population is denied self-determination. Yes, the Indians and the Nigerians did not have votes in Parliament. Yes, the Indians and the Nigerians often had interests very different from those of their rulers who governed from thousands of miles away.

But colonization and the denial of self-determination is not just something that occurs in faraway lands where people look different and speak different languages.

In his 1927 book Liberalism, Mises contends that the denial of self-determination is most certainly not just for people who live in colonial territories. Indeed, self-determination is routinely denied even within polities that are democratic. Mises writes:

The situation of having to belong to a state to which one does not wish to belong is no less onerous if it is the result of an election than if one must endure it as the consequence of a military conquest…. To be a member of a national minority always means that one is a second-class citizen.

In other words, if a person, for whatever reason, is forced to be part of a nation-state or empire in which he does not wish to be a part—even if he can vote in elections—his situation is not fundamentally different from one who has been “colonized” via military conquest.

After all, any group or any “people”—to use Jefferson’s term—which is in a permanent voting minority will indeed find itself at an immense disadvantage. Mises illustrates this in the case of a person who is part of a linguistic minority:

when he appears before a magistrate or any administrative official as a party to a suit or petition, he stands before men whose political thought is foreign to him because it developed under different ideological influences…. At every turn the member of a national minority is made to feel that he lives among strangers and that he is, even if the letter of the law denies it, a second-class citizen.

For Mises, the problem of linguistic minorities was the go-to example, but this framework can be applied to any number of other factors. Minority status could be based on religion, ethnicity, or just ideology. Any “citizen” who finds himself within an group whose worldview is substantially different from that of the ruling majority will be at a disadvantage.

That is, if a small minority group believes that circumcision is an important religious and cultural ritual—but the majority vehemently believes circumcision is in fact barbaric—it is just a matter of time before the minority group’s culture and religion will be gravely threatened.

In other words, this group will have been essentially colonized by the majority. It will be assimilated and subjected to the whims of what is a “culturally alien” power that just happens to be located geographically within the same community.

Limiting the Meaning of Self-Determination

Yet regimes are careful to ignore this problem or deny that colonized populations exist within the borders of the metropoles themselves. In their essay “National Self-Determination: The Emergence of an International Norm,” Michael Hechter and Elizabeth Borland note the inconsistency, and how regimes create an arbitrary distinction between external colonies and internal ones:

That culturally alien rule is deemed illegitimate in colonies but legitimate when it occurs within sovereign states (as in internal colonies) seems both logically and ethically inconsistent; but this is not necessarily so. Because decolonization does not tend to alter international boundaries, it is does not directly threaten existing sovereign states. The secession of a region does cause a shift in international boundaries, however, and thus is represents a potential threat to the territorial integrity of many, if not most, extant states. This fact provides a political rationale for what otherwise appears to be a glaring inconsistency. Although few sovereign states, if any, might be prepared to endorse a principle that could threaten their own territorial integrity, a majority could (and did) vote for this much more restrictive conception of self-determination. (emphasis added)2

I think Hechter and Borland here err in concluding that the inconsistency has been overcome. It’s still there. It’s just that regimes have successfully managed to create the impression it’s been overcome by creating an arbitrary distinction between varying types of colonies. So, when the United States regime conquered and annexed New Mexico and Hawaii, the regime was careful to define these as domestic non-colonial territories.

It’s Not a Colony, It’s the Homeland

The French did something similar with Algeria, although the strategy ultimately failed: as far as the French state was concerned, Algeria was not a colony, it was an “integral part of France” after 1848 and was designed to become like any other French region complete with representation in the national legislature. Thus, France fought hard against Algerian independence both in Algeria and in international forums with other powers. France insisted that the loss of Algeria would mean the loss of core French territory.

The situation was similar in the American southwest. The only difference is that Anglo-American settlers eventually overwhelmed both the Mexican and indigenous populations in New Mexico, thus ensuring the colonized populations could never hope to assert independence or autonomy.

Indeed, the arbitrariness of regimes’ limited conception of self-determination is all the more highlighted by the presence and plight of indigenous populations within settler-majority nations (e.g., Canada, the US, Bolivia, Mexico).

In these cases, we find many groups that are still characterized by culture and language that is separate from that of the majority population. Moreover, these groups are often even tied to specific geographic areas. In the US, for instance, we see this with tribal populations on tribal lands.

Yet, the US regime is careful to never refer to these tribal lands as “colonies” or colonized areas although that is clearly what they are. As suggested by Hechter and Borland, the reason lies in the fact that to label these areas as colonies would give fuel to the notion that, as with African and Asian colonies, these areas deserve self-determination either through full secession or at least through a radical shift toward regional autonomy. To do so would present a threat to the “territorial integrity” of the US itself.

Democracy Will Fix It!

So, it is not surprising that today’s regimes reject the notion that denial of self-determination is even possible along the lines of laid out by Mises. If a religious or ethnic or ideological group finds itself in the minority, regimes insist that self-determination can nonetheless be achieved through “democracy” within the political forms preferred by regimes. This is not a realistic hope for groups that are in a state of permanent minority, however.

Although Western regimes like the United States like to talk a lot about self-determination for others outside the US itself, the regime and its supporters steadfastly deny that the nation contains any minority groups—ideological, religious, or otherwise—that ought to be granted autonomy in the fashion of colonized populations in Africa or Asia. Even when the Left emphasizes the existence of “oppressed minorities” the answer always lies in a larger, more active regime, and in promises of more “democracy.”

- 1. Alberto Alesina and Enrico Spolaore, “What’s Happening to the Number and Size of Nations?” E-International Relations, November 9, 2015.

- 2. Michael Hechter and Elizabeth Borland, “National Self-Determination: The Emergence of an International Norm,” in Social Norms, ed. Michael Hechter and Karl-Dieter Opp (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001), p 199.