Why Americans Would Benefit from a Government Default

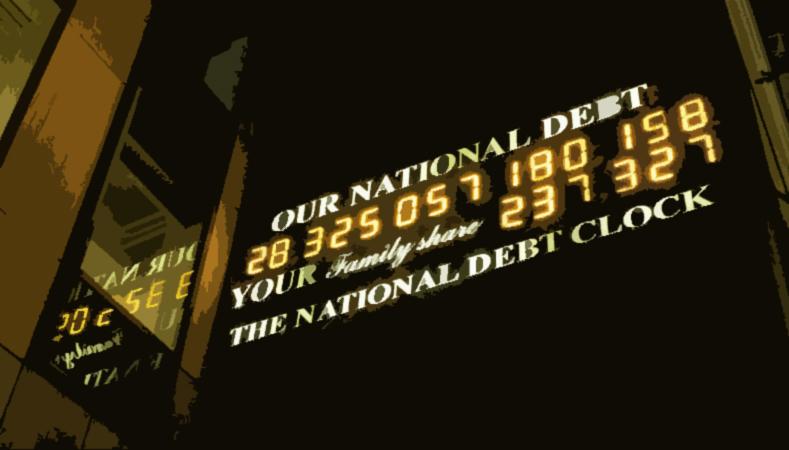

The Biden administration’s rhetoric on the debt ceiling has become nothing short of apocalyptic. The Treasury Department has announced that a failure to increase the debt ceiling “would have catastrophic economic consequences” and would, as NBC news claims, constitute a “doomsday scenario” that would “spark a financial crisis and plunge the economy into recession.”

Apparently, the memo went out to the debt peddlers that they are not to hold back when sowing maximum fear over the thought that the US might government might pause its incessant debt accumulation even for a few days.

The reality, however, is quite something else. While a failure to raise the debt ceiling would no doubt cause short-term disruptions, the fact is the medium- and long-term effects would proove beneficial by reining in the regime’s chokehold on the American economy and financial system.

This is explained in a recent column by Peter St. Onge in which he examines just how much of a problem default really is:

In 2021 the US government plans to spend $6.8 trillion. Of which about half is borrowed — $3 trillion. So if they can’t raise the ceiling, they’d have to cut that $3 trillion.

Mainstream media, naturally, claims this is the end of the world. CBS estimates it would cost 6 million jobs and $15 trillion in lost wealth—comparable to the 2008 crisis, which was also caused by the federal government. CNN, more colorfully, claims cascading job losses and “a near-freeze in credit markets.” They conclude, falsely, that “No one would be spared.”

Considering the source, we can guess these predictions are overblown. So what would happen?

Well, $3 trillion is a lot of money—roughly 15% of America’s GDP. But we have to remember where that $3 trillion came from. The government, after all, doesn’t actually create anything, every dollar it spends came out of somebody else’s pocket. Whose pocket? Part of the $3 trillion was bid away from private borrowers like businesses, and the rest was siphoned from peoples’ savings by the Federal Reserve creating new money.

This means that, yes, GDP would decline sharply. But wealth would actually grow, perhaps substantially. The businesses would be able to buy things they need, while the savers keep their money that was doing useful things like paying their retirement.

So GDP drops, wealth soars.

Now, there will be near-term pain, simply because the GDP drop comes before the private borrowing ramps up, while those retirement savings are no longer being siphoned to pay for parties at strip clubs or, say, another trillion for farting cows.

So, yes, it will be a sharp drop in GDP. But so long as government stays out of the way, choosing the prudent 1920 response of doing nothing, the recovery will be very rapid. Why would they do nothing? After all, governments don’t like staying out of the way these days. Because a government that suddenly loses half it’s budget is going to find a lot of things not worth doing. Given a choice between defunding government workers’ pensions or defunding economy-crushing Green New Deals, governments will choose their own.

So that’s short-term: pain, but less than it seems. And that’s where the magic begins. Because ending deficits fundamentally reduces governments’ long-term ability to prey on the people’s wealth.

This is because debt and money printers are much less obvious than taxes, which are painful and make more enemies. So a default becomes a “back door” to move government back towards its traditional “parasite” role rather than the “predator” role it’s taken on since Nixon unleashed the money printers. Especially since Covid-19, when lockdowns were bought with fresh money and deficits. I wrote about this predatory evolution a few months ago, but the bottom line is government default is a tremendous investment in our future prosperity.

Ultimately, when a media pundit or Janet Yellen predicts the end of the world if debt doesn’t continue to skyrocket ever upward, they are simply calling for a continuation of the status quo.

And what does the status quo mean? It means a world in which the US government continues to spent trillions of dollars it doesn’t have, made possible through monetizing massive amounts of debt and forcing taxpayers to devote ever more of their own wealth and income to paying off an ever-more-huge chunk of interest.

It also means more government spending, which—regardless of whether it’s funded by debt or by taxes—causes malinvestment and through the redistribution of wealth rewards the politically powerful at the expense of everyone else. In other words, its keeps Pentagon generals and Big Pharma executives living in luxury while the taxpayers are lectured about the need to “pay America’s bills.”

Rather, as Mark Thornton noted in 2011, the right thing to do is lower the debt ceiling. Thornton explains the many benefits, ranging from effective deregulation to freeing up capital for the private sector:

If Congress passed legislation that systematically reduced the debt ceiling over time, the economy could be rebuilt on a solid foundation. Entrepreneurs in the productive sectors would realize that an ever-increasing proportion of resources (land, labor, and capital) would be at their disposal, while companies that capitalized on the federal budget would have an ever-declining share of such resources.

Congress would have to cut the pay and benefits of its employees (FDR cut them by 25 percent in the depths of the Great Depression) as well as the number of such employees. Real wage rates would decline, allowing entrepreneurs to hire more employees to produce consumer-valued goods.

Congress would have to cut back on its far-flung regulatory operations, which are in fact one of the biggest drags on the economy due to the burden and uncertainty that Obama and Congress have created in terms of healthcare, financial-market, and environmental regulations. A recent study by the Phoenix Center found that even a small reduction of 5 percent, or $2.8 billion, in the federal regulatory budget would result in about $75 billion in increased private-sector GDP each year and the addition of 1.2 million jobs annually. Eliminating the job of even a single regulator grows the American economy by $6.2 million and creates nearly 100 private-sector jobs annually.

Under a reduced debt ceiling, the federal government would also have to sell off some of its resources. It has tens of thousands of buildings that are no longer in use and tens of thousands of buildings that are significantly underused—about 75,000 buildings in total. It also controls over 400 million acres of land, or over 20 percent of all land outside of Alaska, which is almost wholly owned by the government. There is also the Strategic Petroleum Reserve and many other assets that could be sold off to cover short-term budget shortfalls.

Of course, reducing the debt ceiling would force the government to stop borrowing so much money from credit markets. This would leave significantly more credit available for the private sector. The shortage of capital is one of the most often cited reasons for the failure of the economy to recover.

Lowering the debt ceiling would force federal-government budget cutting on a large scale, and this would free up resources (labor, land, and capital) and force a cutback in the federal government’s regulatory apparatus. This would put Americans back to work producing consumer-valued goods.

Unfortunately, the public has been fed a steady diet of rhetoric in which any reduction in government spending will bring economic Armageddon. But it’s all based on economic myths, and Thornton concludes:

Passing an increase in the debt ceiling merely perpetuates the myth that there is any ceiling or control or limit on the government’s ability to waste resources in the short run and its willingness to pass the burden of this squander onto future generations.