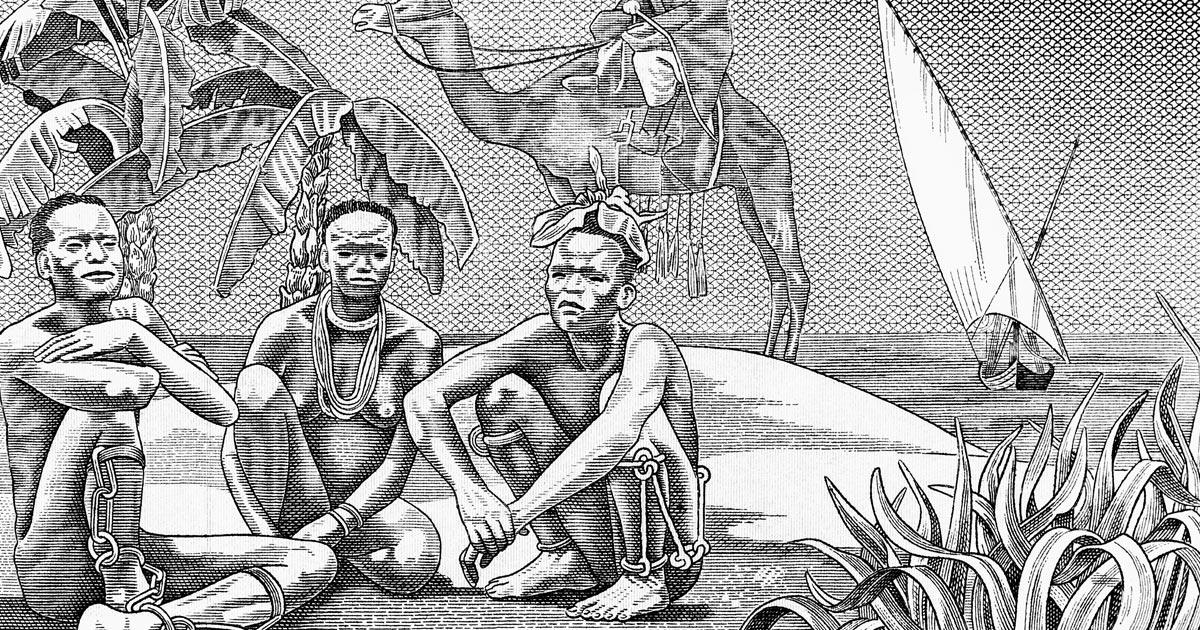

By Compensating Slave Owners, Great Britain Negotiated a Peaceful End to Slavery

The 2018 announcement that the British government completed the payment of a loan that was borrowed to compensate slave owners for the abolition of slavery continues to evoke a flurry of emotions. Many find it outrageous that the British government would contemplate compensating planters rather than the enslaved. Such responses are expected because people are using current moral standards to judge historical realities.

But an appreciation of the sociopolitical events surrounding the loan suggests that compensating planters was a feasible alternative at the time. English laws and customs placed a premium on protecting the rights of property owners, and slaves were considered property. The idea of owning people today seems abhorrent; however, this was not always the case. In British colonies, planters fiercely guarded their right to acquire slaves and appropriate their labor.

Questioning the right to own property provoked contention, even when the property was a human being. This was also the case in the context of indentureship in Barbados, where white indentured workers were perceived as property and could be inherited. British colonies in the West Indies valued autonomy and often resented Britain’s involvement in West Indian affairs.

As a result, when dealing with West Indian colonies, the British government had to tread carefully or face the wrath of the powerful British West India interest. The concerns of West Indian planters were voiced by proslavery parliamentarians in England, who were unwilling dissolve the plantation system without a fight. Politics is futile without compromise, so to abolish slavery, the British government had no option but to negotiate with proslavery forces who saw abolition as a violation of property rights.

Due to the primacy of property rights in England, proslavery lobbyists were able to galvanize the support of nonplanters by arguing that abolishing slavery without compensating property owners would more broadly erode protection for property rights. Their messages were carried by newspapers, journals, and pamphlets admonishing abolitionists for hesitating to compensate enslavers.

Contextualizing the case for compensation, Kathleen Mary Butler shows that the proslavery West India interest employed blackmail to guilt parliamentarians into granting compensation:

The interest argued that successive British governments had condoned and encouraged slave holding…. On several occasions, the Quarterly Review pointed out that various acts of Parliament had encouraged slave owners to spend vast sums of money to buy land and slaves. To deny them compensation, the Review believed constituted a “flagrant breach of faith.”

Jamaican planters weaponized the rhetoric of property rights with equal vigor to bolster the case for compensation. Radical journalist and reformer Augustin Hardin Beaumont, editor of the Jamaica Courant criticized slavery but still noted that enslavers deserved compensation because slavery was enabled by the British and hence it was only fair for British taxpayers to compensate West Indian planters. Throughout the West Indies, slave owners echoed the sentiment that abolishing slavery without compensation was unjust.

These views were so widespread that black slave owners were unwilling to part with slaves unless they received compensation. In 1831, free people of color in Saint Ann Parish, Jamaica, organized a meeting to flesh out the problems of abolition and its effect on property rights. The chairman of the meeting was the prosperous Benjamin Scott Moncrieff, a prominent official who possessed four hundred slaves, owned three estates, and served as an attorney for other properties.

Kathleen Mary Butler reveals that this community endorsed compensation as a tool to safeguard their property rights:

Those attending the meeting objected strongly to comments that Stephen Lushington, the British abolitionist, had allegedly made to the effect that in Jamaica the free people of color had authorized him to emancipate their slaves. The members categorically denied giving any such authorization and stressed their determination to defend their property and surrender it only “for the most full and ample compensation.”

In fact, their resolutions were published in Jamaican newspapers and sent to proslavery outlets in Britain. The historical accounts covered indicate that compensation was a creative strategy to placate enslavers who refused to cede authority to abolitionists. Absent compensation, abolition would have been delayed and blacks would have served remained in slavery for a longer time. Some feel that slaves deserved compensation, but bribing planters was the best tradeoff that the political climate could accommodate.

Yet despite the complexities of the decision, many think that the British owe blacks an apology. However, the truth is that the British atoned for their actions years ago. Britain in 1846 instituted the Aberdeen Act, which intercepted Brazilian ships suspected of trafficking Africans and prosecuted slave traders in British admiralty courts. Historians assert that maintaining the African Squadron alone came at the cost of $6.8 million and the lives of five thousand seamen and officers, who died primarily due to malaria, all in the name of suppressing the slave trade.

The cost of resourcing the African Squadron was also greater than the value of Britain’s trade with the continent. Suppressing the global slave trade incurred considerable expenses for the British, and few appreciate this bold political move that came at the expense of British taxpayers. Indeed, it is ironic that the British are instructed to atone for the slave trade when their counterparts in the Middle East and Africa were coerced into abolishing slavery due to Western directives. Compared to its peers, Britain was a moral superstar and should be lauded for taking a tough stance when others vacillated on the question of slavery.