The Economics and Ethics of Government Default, Part I

Introduction

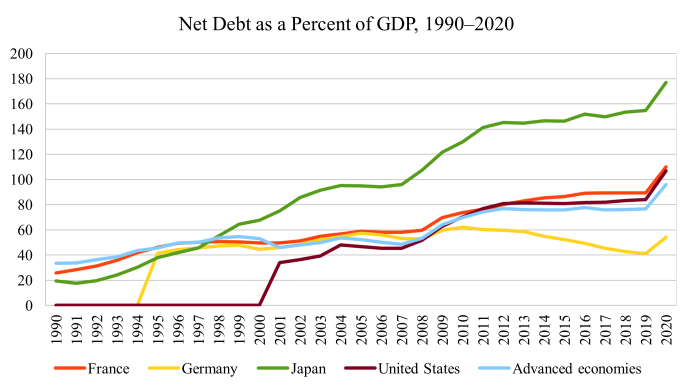

The problem of government deficit spending and the resulting public debt is a challenge to most modern economies. A few states, such as Germany, with a reputation for fiscal austerity, operated with budget surpluses and declining debt, but that was before the coronavirus gave governments everywhere an excuse to massively extend their powers and increase spending. Now it looks like all nations will have to carry the heavy load of paying off enormous government debts contracted in the pursuit of destructive policies. The average net government debt, i.e., debt not owed to some agency of the issuing government, of advanced economies topped 96 percent of GDP in 2020, and there are no signs that governments will stop borrowing.

Figure 1: Net Debt of Select Economies, 1990–2020

Source: IMF. The flat line for the US prior to 2000 is a period of no data.

Across Europe, there is a growing sentiment that public debts are nothing but a burden and should be canceled. Most recently, a group of leftist economists have published a manifesto suggesting that the public debt held by the European Central Bank—at present €2.5 trillion—be written off. This manifesto, however, is simply a thinly disguised plea for inflationary financing of leftist pet projects: not only should the ECB cancel government debts, but the governments should also commit to spending an equivalent amount on a “widespread social and ecological recovery plan.” Although the source of funding for this spending is not specified, realistically it must be borrowed, and the only institution willing and capable of lending such amounts to governments is the ECB.

My objective in this three-part series is not to criticize the suggestions of the manifesto writers, pleasurable though such a task might be. Rather, it is to seriously investigate the problem of government debt and in particular the consequences of government default. What would it mean for the economy if by one fell swoop not just the debt owed to the central bank, but all of it disappeared? I’m not giving too much away if I now reveal that, like Peter Klein and J.R. Hummel, I think that government default would be a great boon to the economy long term.

The idea of solving the debt problem through default is generally considered beyond the pale by all respectable people. As they see it, there are only two alternative solutions: either using inflation to destroy the real value of the debt or introducing economic reforms that lead to an increase in tax revenues, which in turn make paying off the debt manageable. The European manifesto writers therefore deserve credit for raising the idea of debt repudiation.

Before going on to the question of the economic effects of government default, however, we need to first consider the ethical side of things. Economists are loath to accept this, but all policy proposals are inherently normative. It is not possible to act simply as a neutral advisor or to merely suggest policies in the press. There is an implicit endorsement of the ends aimed at and the means chosen in doing this, and we need therefore to ask, first of all, Would it be morally justifiable, in principle, for governments to default?

The Ethics of Public Debt Repudiation

It would seem to be the height of immoral conduct to repudiate the public debt. After all, has not the borrower willingly pledged his person, property, and sacred honor to back the debt? How can any man turn his back on such a pledge without shame? And even if he were to default, would the creditors not have a just claim against his property? The essence of justice is to render to each his own—suum cuique tribuere, in the classic phrase—and since the debt is owed to the creditors, it would be immoral, a sin against justice, to refuse to pay it.

On the contrary, while widespread, such an opinion rests on the acceptance of the basic equivocation that all states use to justify their power. Namely, that the state is a legitimate social institution on a par with other institutions, that it is in fact the most eminent of all institutions, and that consequently its claims and promises are not only legitimate but eminently so. When the state makes a claim on the citizens, these are bound to obey; when it makes a promise to its creditors, it binds not only itself but all the citizens. This, however, is not true: the citizens are subjects of the state and forced into this relation; they are not its sponsors or principals or beneficiaries. Even though virtually all citizens at some point or other benefit from the state, this does not change the basic fact that the state is a violent imposition on all—it is not voluntary and not based on just property rights or other legitimate claims.

Murray Rothbard in his classic case for debt repudiation, first published in 1992, spells out in detail the errors involved in treating the public debt as if it were simply a more sacred form of private debt. Says Rothbard:

[T]he two forms of debt-transaction [private and public debt] are totally different. If I borrow money from a mortgage bank, I have made a contract to transfer my money to a creditor at a future date; in a deep sense, he is the true owner of the money at that point, and if I don’t pay I am robbing him of his just property. But when government borrows money, it does not pledge its own money; its own resources are not liable. Government commits not its own life, fortune, and sacred honor to repay the debt, but ours.

Sanctity of contract, in other words, is a crucial principle of justice, but it does not apply to government promises to pay. For the government does not, in fact, promise to pay: whatever politicos happen to be in charge at the moment simply say to their potential creditors, Lend us money now—and we promise to make the people pay. At no point were the citizens asked for their consent, and it is therefore hard to see how they could be bound by a contract other people concluded. In fact, since it is a contract concluded with the explicit purpose of depriving them of their property, it is difficult to see how it could be considered a valid transaction at all.

A possible objection here could be that the government has the charge of the public good and that while the citizens did not consent to the loans, they are all beneficiaries of the public good provided with the help of such loans. Now, it’s still not clear how a person can be bound by the contract, but leave that aside for now. It’s also not immediately clear that the government is necessary to provide for the common good of all society, especially since it has been shown theoretically and empirically that the most basic functions traditionally attributed to government, peacekeeping and justice, can be just as well provided for in a fully free society without any coercive monopolist. Let’s not delve further into that question here, however. All we will ask is: Did governments in fact contract debts for the common good of all? The answer should be obvious: they borrowed money to fight aggressive wars, finance prestigious public works projects of no more utility than the pyramids, and more recently to bail out and enrich their friends in finance. Most recently, it is true, governments have used borrowed money to bribe the citizenry with handouts, but this can hardly be considered acting for the common good either; especially not when we recall that the handouts are simply meant to disguise the consequences of the destruction of economy and society over this past year. In any case, bread and circuses—or the modern equivalent, stimulus checks—cannot possibly be called the common good but are rather particular goods.

If the state’s creditors have no claim on the tax-paying public, do they at least have a claim on the government, that is, on the assets owned by the state? In some cases, the answer may be yes. Financiers who invested in government debt knowing exactly what they were doing can have no claim—in fact, the question is whether they should not rather be considered accomplices to the crime of taxation, as they so clearly benefited from it (for instance, the primary dealers in the US context). But the average person who, bamboozled, perhaps, by the state’s propaganda, bought a government bond thinking this was an innocent use of his money may have a legitimate claim. Even more so, pension funds pressured to invest in government bonds and banks forced to do so to comply with capital requirements have a legitimate claim to some compensation, not from the taxpayer, but from the government. The problem here, however, is that there is a large group of people with an even better claim, viz., the great mass of oppressed taxpayers.1 These people, the long-suffering producers of real wealth in society, have a much better claim for compensation than the holders of government debt. As a matter of strict justice, any claims the creditors of a bankrupt state might bring would have to wait until compensation has been paid to the taxpayers. Whatever assets remained might then be divided among them.

Conclusion

It would then clearly be just to repudiate the debt. In fact, it is evidently unjust to keep paying interest on it, since each payment is a coerced transfer from the taxpayers to the state’s creditors. Before simply concluding that the government needs to default, however, we need to also take into consideration the economic effects of default. If these were truly calamitous, after all, prudence might dictate that it would be better to suffer the continuing injustice of the debt rather than whatever social deterioration might result from its abolition. In the next installment, we will examine the economic effects of government default in detail.

- 1. We might include those whose property has been unjustly confiscated by the state, but this is probably a minor concern in most Western countries.